HALL OF FAME - 1982

Keke Rosberg

The original Flying Finn was a swaggering swashbuckler whose dashing, daring, darting style of driving enlivened every race he was in. He was a late arrival in Formula 1 racing, having wheeled and dealed and raced his way around the world in other categories for a dozen years, but tried harder than ever to make up for lost time. In the record books his name is not near the top in terms of Grand Prix victories, yet in that select category of those who actually looked as fast as they drove the wonderfully aggressive Keke Rosberg ranks among the very highest.

Keijo Erik Rosberg - he later called himself Keke to make it easier for the media to remember his name - was born in Stockholm, Sweden, on December 6, 1948, where his Finnish parents were students at the time. On their return to Finland his father became a veterinarian and his mother a chemist and both competed in rallies. Their son's first experience behind the wheel came when little Keijo, sitting alone in the family car in the driveway, switched on the ignition and promptly smashed the car into the garage door. Despite that setback he took to karts while still a toddler, greatly enjoyed the wind-in-the-face thrill of it all and by his teens had become an accomplished kart racer.

His goal in life was to become a dentist or a computer programmer but his career path increasingly veered in motorsport directions. Five times he was declared Finnish kart champion and in 1973 he became Scandinavian and European champion. He moved up to Formula Vee and Super Vee and in 1975 won ten of the 21 races he entered. To find other categories to conquer he had to go further and further afield. In 1978 he competed in 41 races on 36 weekends on five continents. Driving for the American entrant Fred Opert, he finished fifth in the European Formula Two championship, second in the North American Formula Atlantic series and, in a similar car, first in the Formula Pacific series.

By this time all plans for a more conservative profession were abandoned and Keke Rosberg's passport listed his job as racing driver. This was a quite legitimate claim since, from his very first race he had never spent any of his own money on his sport and in most years he actually showed a profit. To facilitate this Keke developed what he called his "bread and butter theory: the bread from racing, the butter from elsewhere." Elsewhere usually took the form of marketing himself to sponsors, selling them a patch on his suit or a space on his car, then performing various duties as a salesman for whatever goods or services he endorsed.

Yet no amount of financial savvy could buy a driver a ride in a front-running Formula 1 car and when Keke made his debut, in 1978, it was in an ill-handling and underpowered Theodore, in a team fielded by wealthy Hong Kong businessman Teddy Yip. "An absolute pig of a car" was Keke's description of the Theodore and his subsequent machinery in a succession of uncompetitive teams - ATS, Wolf, Fittipaldi - warranted similarly faint praise, no matter how hard he drove.

By this time Keke was 33 years old and while his lifestyle was continually improving (he eventually had a Lear jet, a penthouse in Munich, a country mansion in England, a chalet in Austria and a villa on Ibiza where he spent most of his time) his Formula 1 career was going nowhere fast. The low point came in 1981 when the Fittipaldi team's money ran out and it seemed Keke Rosberg was destined to become a Formula 1 has-been who never really was.

Meanwhile, at the front of the Formula 1 field, the 1980 champion Alan Jones unexpectedly announced his retirement and Frank Williams was forced, at the last minute, to hire the only reasonably competent driver available: Keke Rosberg. Ever the opportunist Keke seized the opportunity with both hands and, though he only won a single Grand Prix (at Dijon in France), he proved he could drive as consistently as he could quickly and piled up enough points to become the 1982 World Champion.

That year, in which any one of half a dozen drivers could have won the title, Keke said he "drove every lap absolutely flat out." The next year, when the turbo-powered cars reigned supreme, and he still only had a normally aspirated Cosworth in his Williams, Keke drove even harder: "I was probably the fastest I'd ever been in my career. I just refused to accept that anybody could beat me and to stay with the turbos I was prepared to take massive risks."

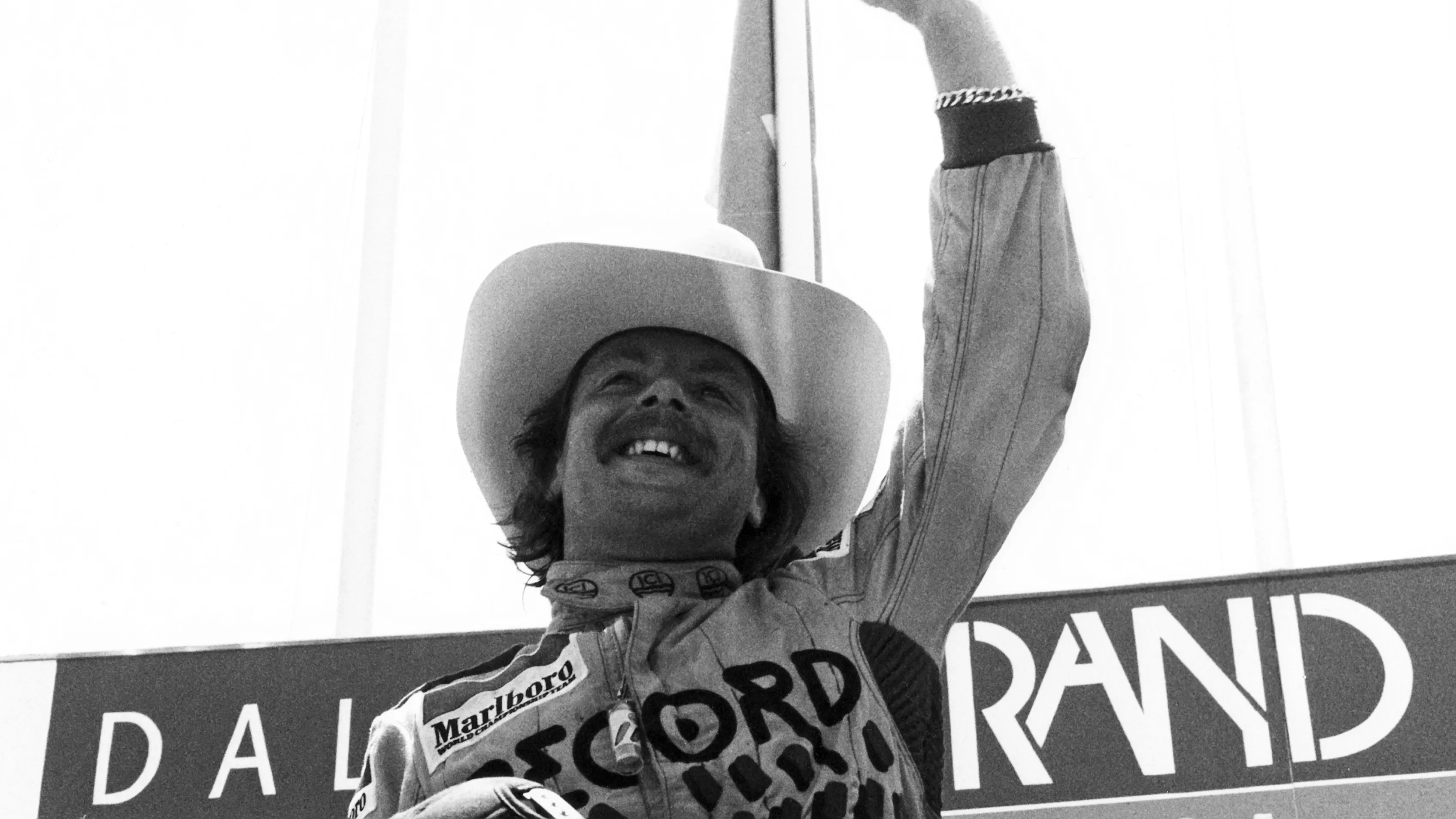

And it showed, which is why he was so noteworthy as a driver and equally compelling as a personality. "I'm a cocky bastard," he would say, "and I know it." He affected an aura of bravado and cut a dashing figure to match. With his flowing moustache, untamed mane of long blond hair and swaggering walk he resembled a swashbuckling pirate who might plunder and pillage for pleasure. He used his car like a sword, swinging it about ferociously, cutting a swathe through the corners, kicking up dust, grass and tyre smoke and carving great chunks of time out of each circuit. The chain-smoking Flying Finn was even more spectacular when Williams got Honda turbo engines. His sensational pole lap for the 1985 British Grand Prix – in which he averaged 160mph around Silverstone - was not only then the fastest-ever lap in Formula 1 history, but also one of the most exciting.

But Keke scared himself on that occasion and eventually burnt himself out from the wear and tear of his all-out-all-the-time approach that was not conducive to longevity in comparison to the greater circumspection employed by such long-serving champions as Niki Lauda and Alain Prost. "My style of driving is probably more wearing than theirs," Keke said. "Playing defensive tennis is less taxing than playing attacking tennis."

When he retired from Formula 1 racing, after moving from Williams to McLaren for the 1986 season, Keke continued competing for several years in sportscars (with Peugeot in 1990 and 1991) and touring cars (with Mercedes and Opel in the German DTM series) and also ran his own teams in several categories. He became a successful driver manager, masterminding the careers of, among others, fellow Finn and champion Mika Hakkinen and then, with a paternal interest in his future, Keke looked after a youngster named Nico Rosberg.

He managed the early career of his son, then deliberately stepped back to let the boy fend for himself. Keke continued to offer advice, sending Nico brief inspirational text messages: ‘Pedal to the metal! Push!’

When Nico Rosberg became the 2016 World Champion, 34 years after his father won the driving title, they celebrated together, tearfully. “Yes, we’re emotional because to us it’s a family sport”, said Keke Rosberg. “Nico knows what it means to me and to him.”

Text - Gerald Donaldson