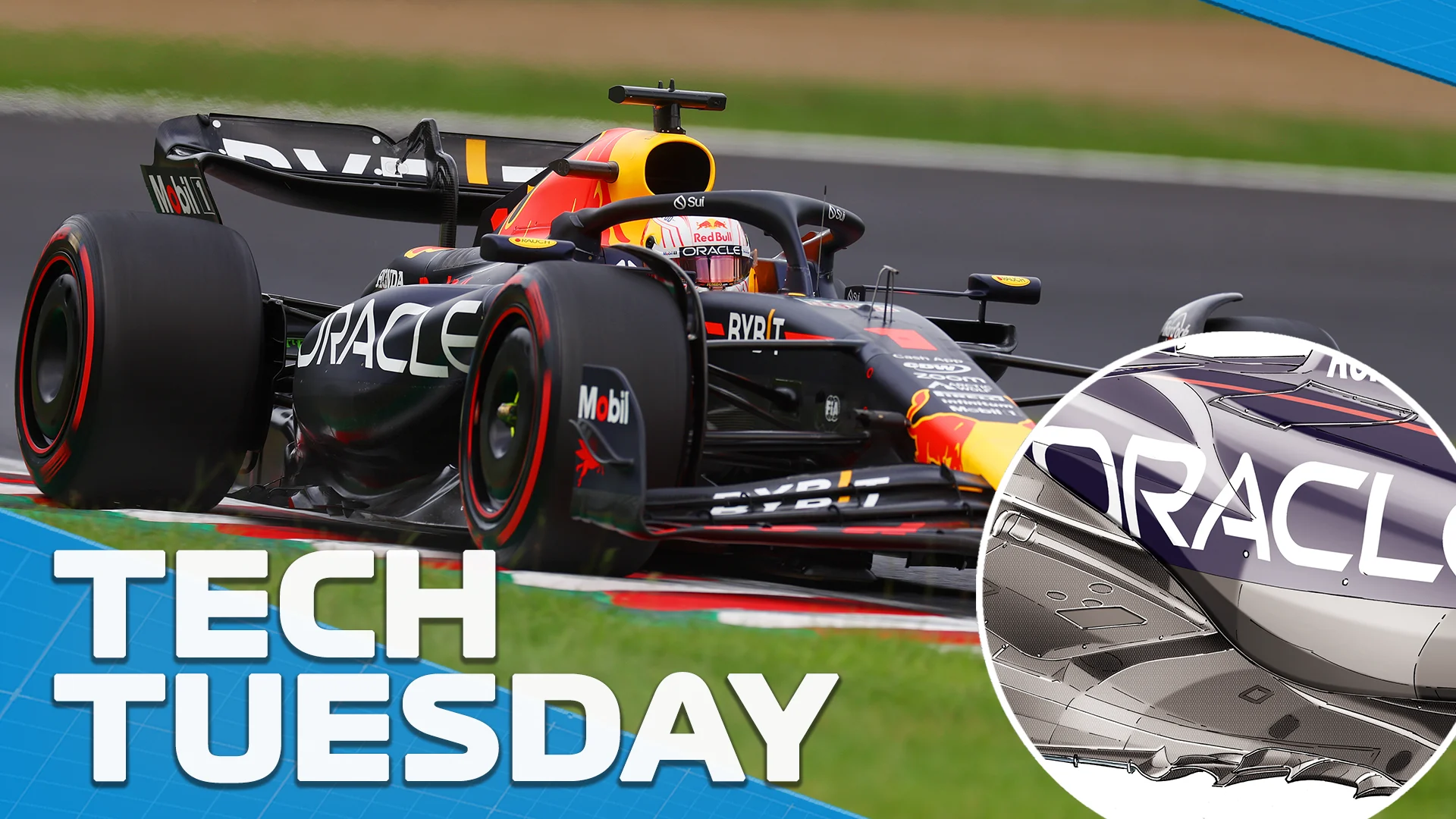

TECH TUESDAY: The main factors behind Red Bull’s Singapore slump and how they bounced back in style at Suzuka

Red Bull’s spectacular fall from domination in Singapore and its equally spectacular return to form in Suzuka has highlighted just how hyper-sensitive this generation of cars are to set-up – specifically regarding ride height.

The ground effect principle by which these cars generate a big proportion of their total downforce is dramatically more effective the closer the lowest point of the floor is to the ground, until it becomes so low that the airflow stalls.

Next Up

Related Articles

Stefano Domenicali attends Apple TV press day

Stefano Domenicali attends Apple TV press day Why Hadjar’s mum knew about Red Bull seat before he did

Why Hadjar’s mum knew about Red Bull seat before he did Hamilton feels ‘winning mentality’ at Ferrari ‘more than ever’

Hamilton feels ‘winning mentality’ at Ferrari ‘more than ever’ ExclusiveWhy Piastri expects to keep Norris on his toes again

ExclusiveWhy Piastri expects to keep Norris on his toes again.webp) Who do you think will get the regulation changes right?

Who do you think will get the regulation changes right?.webp) Verstappen encouraged as Red Bull ‘hit the ground running’

Verstappen encouraged as Red Bull ‘hit the ground running’