TREMAYNE: The tragic story of Mark Donohue – The American racer with a streak of steel behind his ‘Captain Nice’ nickname

.webp)

They called him ‘Superman in Blue’ or ‘Captain Nice’. American driver Mark Donohue was a key part of the fabric of Roger Penske’s racing operations in the late 1960s and early 70s. If you wanted a race car sorted, Donohue and Penske were your men. And if you wanted it driven to victory... well, Mark would handle that for you, too.

Over in the USA, he and Roger had built the same sort of tight, fraternal relationship that Colin Chapman enjoyed in Europe with Jimmy Clark.

READ MORE: Why F1's quiet champion Jim Clark remains a legend

But where Clark often had to put up with Lotus’s lack of reliability, Donohue and Penske worked tirelessly in the development and preparation of their race cars, driven by their simple yet famous maxim: In order to finish first, first you must finish.

Mark’s professional career had its roots in 1962 when he was accepted into the Road Racing Drivers’ Club after some excellent amateur performances in his own machinery, and became close friends with established American racing star Walt Hansgen.

Mark took to hanging out at Walt’s car dealership and the two bonded over their love of engineering (Mark had gained his degree in mechanical engineering from Rhode Island’s Brown University), and their concerns over safety.

Both believed passionately that road racing was a sport, and that it was better not to try resolving problems with words but by saying nothing at all. Instead, they listened to what their cars were telling them, and acted accordingly.

Walt tutored many upcoming drivers and was the first to really see Mark’s talent. He invited him to share John Mecom’s Ferrari 250 LM at Sebring in 1965, which Mark cited as his big career breakthrough, and Walt threatened not to run for Ford at the Daytona 24 Hours in 1966 if they didn’t accept his rookie pal as the co-driver of his Holman Moody GT40.

They finished a restrained third (Ford favoured Shelby American to take the first two places), and after Walt’s death testing an Alan Mann Racing GT40 at Le Mans that April, Mark started his remarkable alliance with Penske.

Mark’s autobiography, written by Paul Van Valkenburgh, was called The Unfair Advantage because that’s what he and Roger always sought when they were racing.

It didn’t actually tell his life story, but instead chronicled just what he did as he worked on each of his race cars, imparting many of the technical secrets behind their success. With his innate humility, he simply couldn’t have told it any other way.

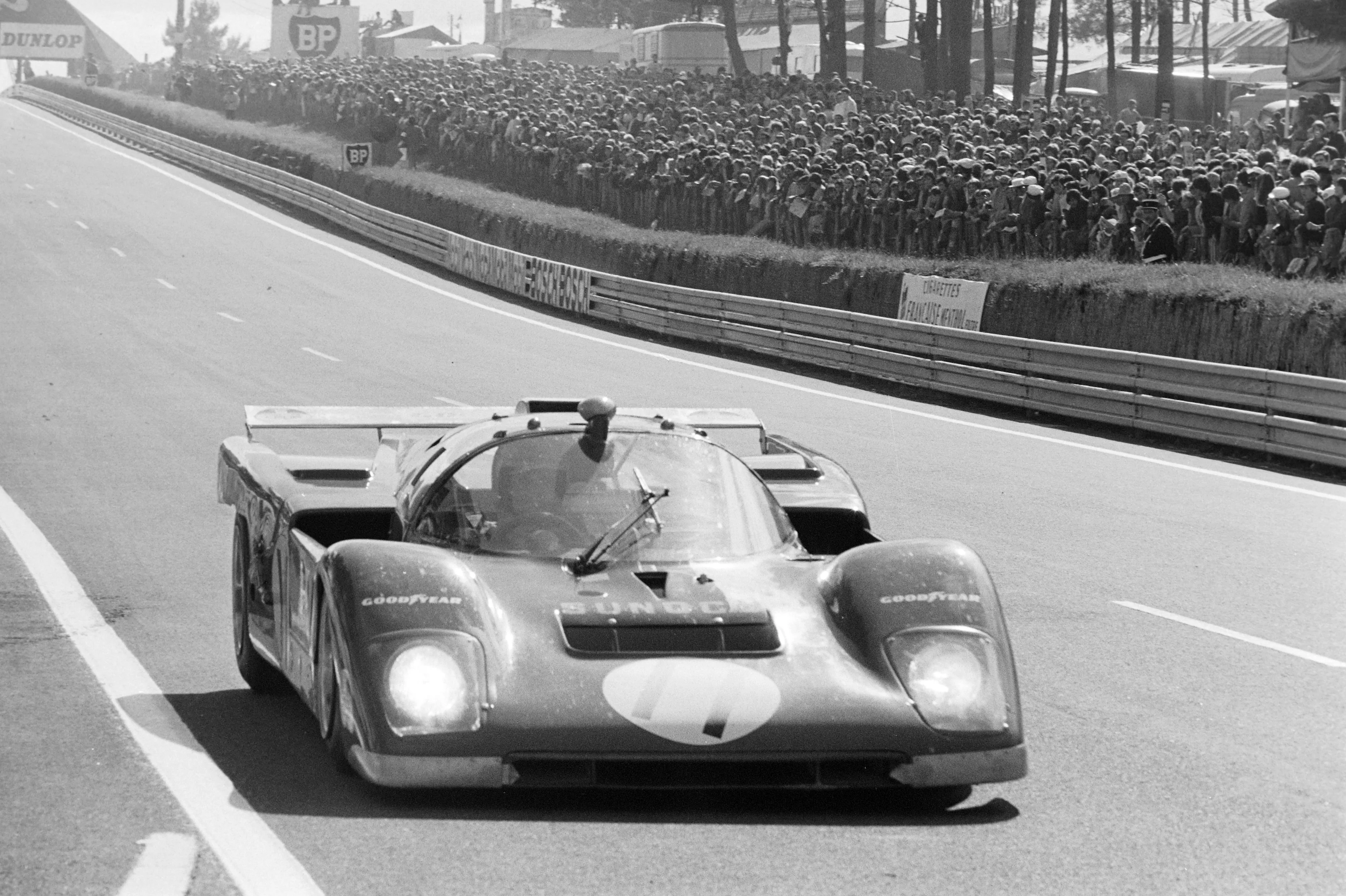

Like Dan Gurney and Mario Andretti, he was one of the greatest genuine all-rounders the sport has ever seen. He shared a Ford MKIV with Bruce McLaren to finish a delayed fourth at Le Mans in 1967, and with Roger was Rookie of the Year at Indianapolis in 1969.

He helped McLaren to sort out their tricky M19A and took third place (behind only winner Jackie Stewart and Ronnie Peterson) on his F1 debut in the rain at Mosport in 1971, and at Indianapolis in 1972 he was the first man to win the 500 in a car bearing Bruce’s name, with the M16B.

They also won the USRRC Championship, sorted various Lolas to win US F5000 races, won the Trans-Am series, the first International Race of Champions, and, best of all, the CanAm series in 1973 with the 1200 bhp Porsche 917-30 super monster.

But that engineering nous added the extra dimension that had also made Walt and Bruce such standouts.

And yet, towards the end of his life Mark was also being nicknamed ‘Dark Monohue’ by insiders who saw the effect on him of his decision to retire at the end of 1973. He was troubled by anxieties over what a racing driver became when he was no longer racing, and doing the thing that he most loved doing in life.

So when he was invited to spearhead Penske’s F1 project later in 1974 it was an easy decision to make a comeback. The challenge was irresistible, from both the engineering and racing viewpoints.

READ MORE > F1 IN AMERICA: The curious case of the first United States Grand Prix

Sadly, the Penske PC1 was a lower midfield F1 car, and halfway through the 1975 season the old insecurities were returning. It was two seconds off the pace, and that further compounded the challenge of racing on tracks with which his rivals were already super-familiar, but which to the Penske team were new territory every time. Mark, ever hard on himself, took on much of the blame.

“That was probably one of his biggest hang-ups,” Roger said in the revised edition of The Unfair Advantage, “that he would be too hard on himself. And I guess that was one of my jobs, to try to kick him in the pants and say, ‘Hey, let’s go racin’ here. There’s a lot more to this than a bad day or a good day.’”

Legendary team manager Carroll Smith avowed: “Mark was a complete racer. That’s what people forget about him – there was a lot of tiger in him. He gave too much credit for his success to his engineering ability, and not enough to his driving ability. I don’t think he ever realised just how good a driver he was.”

Backing that up, Smith recalled the time he and Roger watched, jaws dropping, as Mark had hustled the unloved AMC Javelin Trans-Am racer flat out down the hill past the pits at St Jovite. At the time nobody had ever done that.

READ MORE: The story of America's lesser-known Grand Prix winner

When he had won that inaugural IROC series in 1973–74 where drivers raced identical Porsche RSRs, Mark had fair and square beaten the likes of AJ Foyt, Emerson Fittipaldi, Richard Petty, Denny Hulme, Peter Revson, Bobby Unser, Gordon Johncock, Bobby Allison and David Pearson, as he won three of the four races – two at Riverside and one at Daytona.

The decision to switch to a proprietary March 751 – something that never troubled Roger whenever his team had to fight their way out of trouble – proved a major boost by the British GP in mid-1975.

He finished fifth in the rain-spoiled race, matching his previous best result in the unloved PC1 in Sweden where he had battled hard with reigning champion Emerson and rising star Tony Brise. Things were beginning to look up at last, now that he had a competitive car with which he believed he could start showing the team’s proper form.

Soon after two punctures had nixed his chances with the March in Germany, on August 9 he was at the banked 2.66-mile Talladega Superspeedway in Alabama, where he took the 917-30 to a remarkable closed-course speed record of 221.120 mph, despite the imminent onset of rain in the horribly humid conditions.

The big Porsche had slithered on the edge of adhesion at speeds approaching 250 mph on the straights, before Mark guided it smoothly through the turns. He confided to his friend, acclaimed writer Pete Lyons, “It was difficult.” And then added: “It’s the only thing I’ve accomplished this year.”

Four days later he and the Penske team headed to Austria for the Grand Prix at the challenging Osterreichring, prepared to give it his all to achieve something else. But various problems saw him qualify only 21st, just behind Andretti.

After a lengthy conversation with Mark prior to the Sunday morning warm-up, the latter told Mark’s much-missed biographer Michael Argetsinger: “He was very lonely over there. ‘I wish I was in your shoes,’ Mark told me. ‘After this race you get on a plane, you’re home with your family and you’re racing in the States next week.’ I was surprised how much he wished he was doing it the way I was doing it.”

Soon afterwards, a failure of the front left tyre put the March off the road on the rise approaching what became known as the Hella Licht corner at 150 mph. It slithered into the catch-fencing, which rolled up and acted as a launching ramp, and struck advertising hoardings after clearing the guardrail.

A pole struck him a hard blow to the head, momentarily knocking him out, though Emerson Fittipaldi told this writer that he had held a lucid conversation with him in the immediate aftermath.

But as a headache persisted Mark was flown to the Landeskrankenhaus hospital in nearby Graz. There, despite a four-hour neurosurgery to remove a blood clot, he succumbed at midnight on the Tuesday.

America lost one of its greatest drivers, before he had the fresh chance he so desperately sought to remind the F1 circus what he could really do in a Grand Prix car.

‘Captain Nice’ – could that really have been an appropriate nickname for a hardened professional racer so intent on winning? Mark himself didn’t like it, and told a reporter, “I never believed that Captain Nice stuff. I always was told that nice guys finish last.”

But friends spoke of his shyness and reserved manner, which opened up when dealing with fans and media, and the warmth of his offbeat sense of humour. And the things he did that few got to know about.

After Walt’s death Mark had set up the Walter E Hansgen Memorial Foundation engineering scholarship at Brown University. And, without fanfare, he had continued to correspond with a six-year-old fan, replying personally to every letter he sent.

And the great Brian Redman said: “He was a hell of a driver, but more important he was just one great person.” And later he told Argetsinger: “He was correctly known as ‘Captain Nice’. Of course, under that pleasant exterior there was a streak of steel. But he was a great guy and will always be an American hero.”

Most of all, his peers spoke of his talent as a race driver even more than as an engineer. Mark won 119 of his races, an impressive 38 percent strike rate.

After his death, Roger Penske seriously considered quitting racing. Instead, he characteristically carried on and, one year later at the Osterreichring, John Watson scored the team’s sole F1 victory – one of the most poignant in F1’s rich history – in the Penske PC4.

Today Penske Racing remains a huge force in American racing circles. “I regard Mark as the catalyst for all that we have achieved,” Roger told Argetsinger. “He set the standard.”

Next Up

/Winners%20&%20Losers%20DISPLAY%20template%20(1).webp)