Mercedes arrived in Japan with a new barge board update designed to get them back on an even keel with Ferrari, after the Scuderia had won three of the four previous races. And with Valtteri Bottas securing an assured win at Suzuka, the upgrade looked to have done the business, as Mark Hughes and Giorgio Piola explain…

One of the key distinguishing traits between the two opposing front wing philosophies generated by this year’s aero regulations is that between peak downforce and downforce sensitivity – i.e. how consistent the downforce is in a range of different operating conditions.

As we detailed after the first pre-season tests, the two philosophies were neatly represented by Mercedes and Ferrari. The former favoured a loaded outboard end of the front wing, utilising the full allowable depth for the outer end of the elements. By contrast, Ferrari favoured a relatively unloaded outboard end, with the elements bunched up at the outer ends.

Almost every team looked at both alternatives during the initial assessments of the revised aero regs for this season and they all agreed there was a definite trade-off between the two ideologies. The loaded outboard wing gave greater peak downforce. The unloaded outer wing gave a more robustly consistent downforce.

The Mercedes aero department was able to ameliorate the biggest downsides of the loaded outboard wing through very intricate control of the flow down the whole car. It was helped in this by its existing long wheelbase/low rake philosophy. Relying less than, say, the Red Bull on the angle of attack of the floor to create underbody downforce and more on having a bigger floor area to create the downforce, made the Mercedes aero inherently less sensitive. This in turn seems to have made the loaded outboard wing more feasible.

READ MORE: Analysing the top three teams’ 2019 car designs

Red Bull, with a shorter and higher-rake car, opted for the loaded outboard wing too – and it took half a season of development before its aerodynamics could be tamed as it gave wildly varying downforce levels through different parts of the corner.

The downside of Ferrari’s front wing design was that the total downforce was less – and the front downforce in particular was lacking, giving the team difficulty in getting the car balanced

Ferrari, in opting for the unloaded outer front wing, were able to generate greater outwash around the front tyres, which helped keep the flow down the car attached in a wider range of conditions (a wider range of speeds, roll angles, wind conditions etc.). But with the downside that the total downforce was less – and the front downforce in particular was lacking, giving the team difficulty in getting the car balanced.

These basic traits have defined the development paths of each of the top three cars.

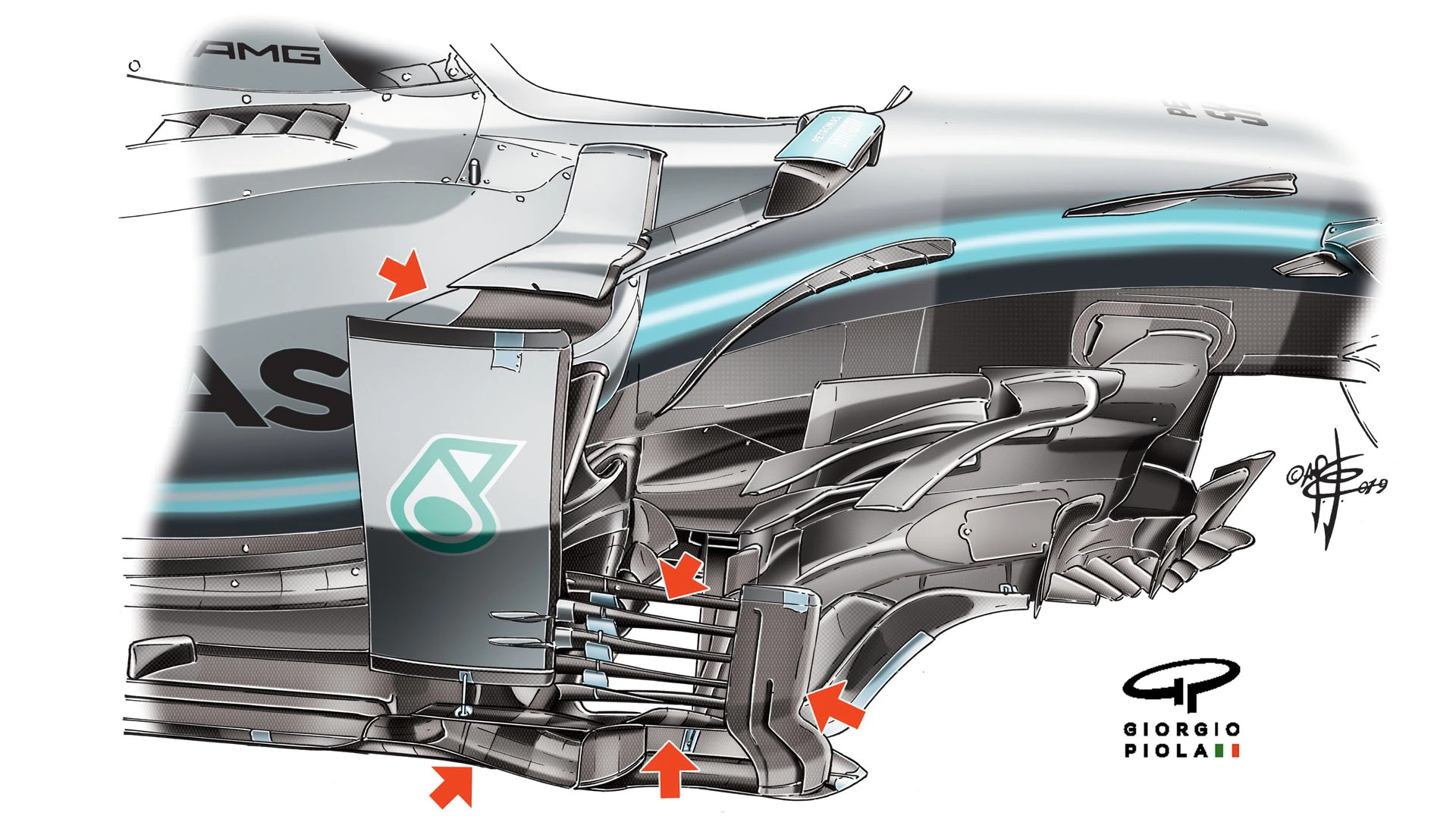

Following Ferrari’s enhanced front end at Singapore, which moved the centre of aerodynamic pressure forwards (to the great benefit of the car’s balance), two races later Mercedes showed up at Suzuka with a further refinement of the big update it brought to Hockenheim. This again centred around the barge boards.

The Hockenheim upgrade was about making the loaded outboard front wing slightly less extreme, changing the emphasis away from direct front wing downforce and increasing the total downforce by enhancing the airflow from the inboard part of the wing and through the barge boards.

At least that’s what the tunnel and other simulation tools told them had been achieved. In the real world, the Hockenheim update never did quite deliver what the tunnel promised, as the race team found that it was now more difficult to find the car’s set-up sweet spot.

READ MORE: Analysing Mercedes’ Hockenheim upgrade

The Suzuka upgrade appears to be a refinement to that of Hockenheim, to give a more robust representation in the real world of what the tunnel promised. As such, the big shoulder vane which helps direct the flow from the barge boards down the sides of the body (keeping it from spilling out towards the outwash airflow created around the wheels) has been split and no longer has a join between the vertical and horizontal.

This suggests that the previous version may have been inducing a pressure build-up, slowing the speed of the flow through there. If this speed is too slow, it will tend to induce airflow separation under certain conditions, reducing downforce at the rear.

The distinctive slotted vanes joining the back of the barge board with the shoulder vane have been increased from three to five, again suggesting that the previous arrangement may have been prone to a pressure-induced blockage. These slots bleed out the excessive flow and feed it into the outwash airflow.

Trackside Performance Analysis: The art of tackling Suzuka’s Esses

During Friday practice in Suzuka – a circuit that heavily rewards cars which can maintain big downforce through the long, fast corners – the Mercs looked dominant. But in the very gusty conditions of qualifying, the Ferraris were the more drivable cars, as the benefits of that less sensitive downforce were accentuated. Together with their usual straightline speed advantage, it allowed the Ferraris to lock out the front row.

Next Up

Related Articles

.webp) ExclusiveHow Aston Martin are reacting to their pre-season struggles

ExclusiveHow Aston Martin are reacting to their pre-season struggles Listen to Carlos Sainz's interview on Beyond The Grid

Listen to Carlos Sainz's interview on Beyond The Grid F1 TV announces 2026 presenter line‑up

F1 TV announces 2026 presenter line‑up The family tree of F1's 11 teams and how they came to be

The family tree of F1's 11 teams and how they came to be Betting2026 season match bet predictions and H2H battles

Betting2026 season match bet predictions and H2H battles Unlocked5 of the best young drivers waiting for an F1 chance

Unlocked5 of the best young drivers waiting for an F1 chance