The intersection of technology and management science

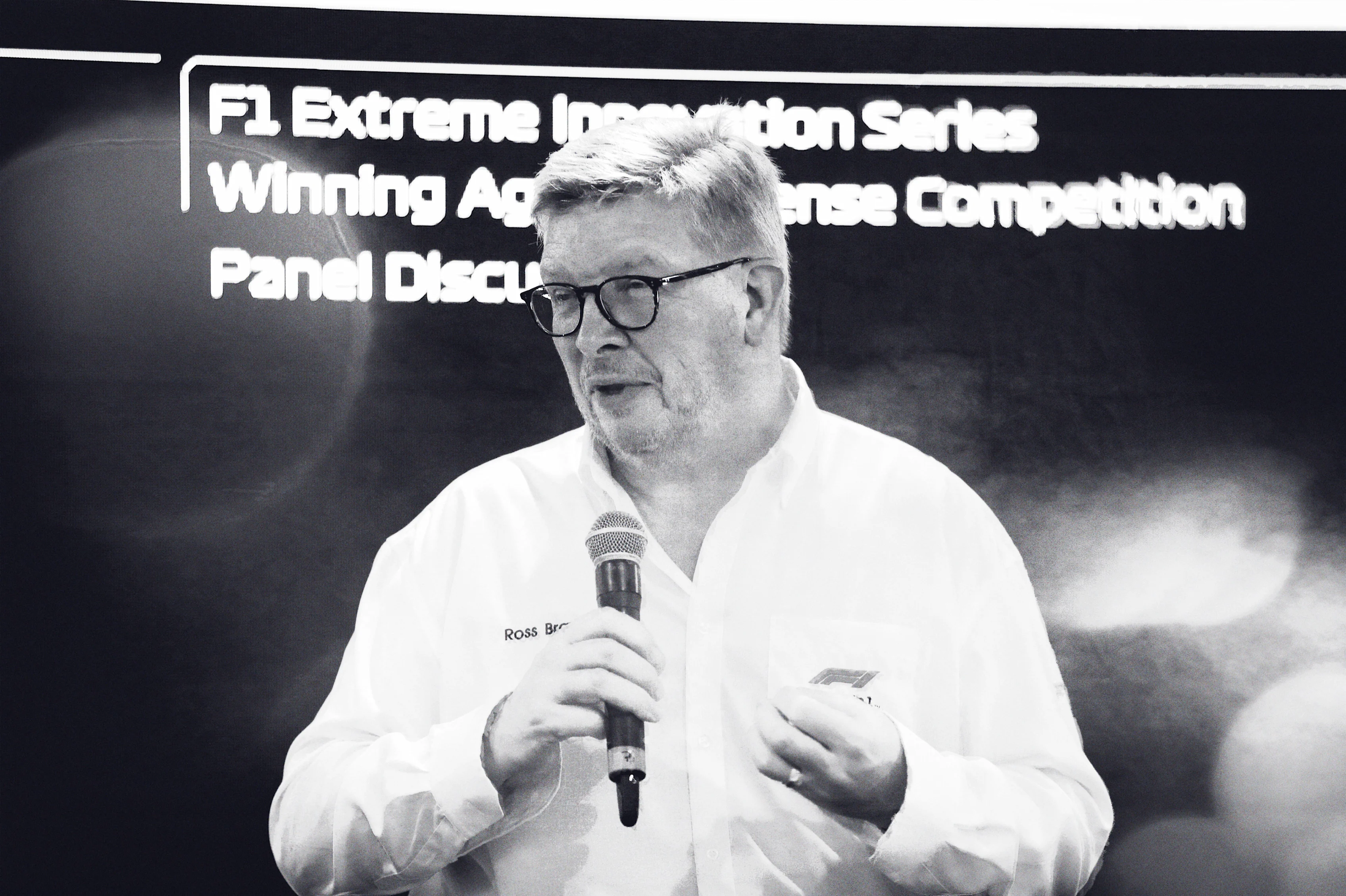

F1 managing director Ross Brawn and MIT senior lecturer Ben Shields reveal some of the insights to be shared at an exciting new series of business innovation events

Imagine if your business had to publish its performance reports publicly, to the whole world, every fortnight. Or where millions of people got to see your board meetings in action – and they were held 21 times a year. Or where every single person in your organisation, from data scientists to the canteen chefs, could be directly responsible for the profit or loss of millions of dollars. The business is, of course, F1 – and it sits at the apex of technology and management science.

It’s long been said that other organisations can benefit from the rapid ‘always in beta’ culture that is at the heart of F1 and now a series of events called F1 Extreme Innovation Series, held at iconic F1 racetracks, will see a selection of top business leaders attend to gain insights from both F1 experts and faculty from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Sloan School of Management.

Following the inaugural event (held at Monza on 30 August) and ahead of the next event at Austin on Thursday 18 October, F1’s Ross Brawn and MIT’s Ben Shields revealed some of the insights that attendees can look forward to.

F1 has given many innovations to the real world – what are seen as the most impactful?

Ross Brawn: On the technology side, there are composite disc brakes. These were first seen on F1 cars before hitting the mainstream in the high-performance car market.

The use of carbon fibre also started with F1, thanks to designer John Barnard in the 80s, who created the first carbon fibre chassis. When it launched everyone assumed that when a carbon fibre chassis hit a wall it would vaporise into grey powder – but that clearly wasn’t the case! It was a much more resilient structure than they had at the time and became the basis of the survival cell that now operates in F1 and has saved many lives.

Telemetry systems, too. We’ve been using them for decades but now applications have been found in other sectors, such as a train company working with McLaren Applied Technologies. The usage of telemetry is a vital tool to increase efficiencies and safety. There are some unusual uses too. Williams looked at open sided refrigerated cabinets, the ones you see in supermarkets. When studying the airflow they found gross inefficiencies in the way the air flowed around the cabinet. By using aerodynamic simulation tools they made massive efficiencies in the cost of operating a chiller cabinet.

Ben Shields: F1 is the ultimate petri dish with relevance to so many management disciplines: operations, marketing, organisation studies, strategy, innovation, finance, entrepreneurship. It sits at the intersection of technology and management, as does MIT.

Take the notion of the 4th industrial revolution. Formula 1 – as a sport and a business – is a fascinating case study to understand the implications of major technological shifts. For example, we are continuing to negotiate how humans and machines collaborate, how machines augment the work of humans and how humans best deploy machines for specific tasks. The relationship between the driver and the car, which is a highly sophisticated digital system, is one place to study human-machine collaboration. On the commercial side of F1, the sport is building from scratch new digital platforms and experiences to exceed the expectations of today’s sports fans, and there is much other companies can learn about digital transformation from studying their journey.

What are the management features of a modern F1 team that create the conditions for consistent extreme innovation?

Ross Brawn: Our performance is measured constantly – car, driver and team. After every race we know where we are. It’s a constant feedback loop. And unless you have the optimum set-up, then you may progress but not enough and the others will pull away from you. You go a half second faster but they go one second faster. It’s highly pressured but also rewarding.

I remember when I was an engineering design apprentice and I might design a component which didn’t go into production for several years. But when I designed racing car parts they’d often be finished the next day. That rapidity is demanding and asks for huge commitment, but it also gives you a regular reward.

Of course, we in F1 could also learn from business leaders in other sectors. We tend to be very focussed on the technology and that can make us quite insular and blinkered to other aspects of performance. I’m sure there are areas of training and personnel development that would benefit us – and there may be areas of technology we are not familiar with.

Ben Shields: A common misperception is that all innovation comes from the mind of a brilliant thinker who invents an idea out of thin air. F1 teams don’t necessarily work like that. They have a disciplined process for innovation that combines both rigorous science and teamwork. Constant data collection and analysis are embedded in the way they work. They also have strong leaders who are able to get the most out of their people in high-pressure situations.

Remember that no race is the same. Different cars, different tracks, different weather conditions. F1 teams have no choice but to innovate, especially as new rules are introduced each season. It’s adapt or lose. F1 teams innovate consistently by adhering to scientific method. They identify the problems they have to solve, build hypotheses around them, and then they test, analyse and iterate. You see this method in both successful technology companies and F1 teams, and it’s all enabled by human collaboration.

How important are mentors to your business?

Ross Brawn: I have lots of friends and colleagues who are successful entrepreneurs and business people in their own fields. I’ve often faced a challenge in F1 and sought the counsel of these friends who work in different environments. In F1, one of my most important mentors was Patrick Head, technical director at Williams GP. He taught me the value of imposing high standards on engineering quality, and a single minded approach to performance that made Williams GP such a successful team in that era. He was tough and demanded a great deal of his people and I was fortunate to work for him. In fact, he gave me my first job in F1.

I also spent a lot of time at Imperial College in London because our aerodynamic program in the early days of Williams GP was run through the college. It was run in conjunction with Dr John Harvey and Professor Peter Bearman and they helped me understand the principles and theories of aerodynamics. At the time I was heading up a small three-person department.

It was a little like the blind leading the blind, in some ways – because aerodynamics was poorly understood by the teams in those days. John and Peter really helped to unravel the mysteries and that was partly why Williams was so competitive back then because we were beginning to understand how crucial the aerodynamic performance of the car was. I particularly remember a eureka moment when we built a wind tunnel car with venturi tunnels, utilising ground effect, each side of the chassis. The model generated three times the level of downforce than the car we were racing at the time. We went on to win the world championship with that car, and those Imperial College Professors played a huge part in that.

Is there a learning from F1 that you think will particularly resonate with business executives?

Ben Shields: I think one of the main lessons that the management community outside of F1 can take from the sport is around data-driven decision making. Executives are awash with data. But F1 teams are very specific and intentional in how they use data to guide strategy. In addition, some companies often silo data within their analytics teams, while F1 teams integrate multiple sources of data into the decision-making process. In short, F1 is an exemplar of a data-driven organisation.

The teamwork inherent in F1 must also serve as a good example to other businesses?

Ross Brawn: Yes, communication and feedback are vital. For instance, we always have a post-race debrief looking at where we are, what we need to do and what is each person’s role in making that happen. You might have 300-400 people in an engineering group of a F1 Team, all of whom have to pull together in the right direction and at the right time.

The continuity of the team is invaluable here. Once you have a core team, they know the lessons learned from the previous car and the next steps. Each car is an evolution and you don’t have to reinvent the wheel every year.

You need to communicate and share the overall objectives with everyone on the project, otherwise they can get siloed. They may think, for example: “I’ll make the best gearbox possible”. Which sounds fine, until you realise that a gearbox that’s 1% more efficient might make the aerodynamics 2% worse because it is bigger or the wrong shape. It’s the overall integrated car performance that is crucial.

Ben Shields: The technical innovation in F1 often gets the headlines, but in many ways, the people part of the equation is just as compelling. Teams are comprised of highly talented people who must work together under tight timelines to achieve specific and measureable performance goals. They must also work together to constantly innovate and develop new solutions to a dynamic set of challenges. For leaders who are managing their own high-performance teams, much can be learned from how F1 teams operate, manage conflict, and engage in creative problem solving.

Finally, what will make the F1 Extreme Innovation Series events unique?

Ross Brawn: I think F1 teams will definitely benefit from our collaboration with MIT. It’ll give them a wider understanding of the world of technology, engineering and management. As I said, F1 can be insular, just comparing themselves to other F1 teams. This is an opportunity to learn things that will make the teams stronger.

Ben Shields: The ability to attend the events at F1 circuits is truly unique – participants are right above the pits, in front of the team paddock, right in the heart of the F1 world. Touring the track, the pits and the paddock really deepens the individual learning experience.

I hope everyone will learn something new and how to apply it to their organisation to create real change – whether that’s sharpening your strategy or managing your organization more effectively. Crucially, it will also be fun. Because learning should always be fun.