In the second in our series remembering classic strategy calls in F1 history, we go back to 1958 and a time when putting an engine anywhere other than in front of the driver seemed, to many, a bizarre concept ("The horses pull the carriage, not push them,” quipped Enzo Ferrari famously). But a new era was on the way, thanks in part to an ingenious strategy call by Stirling Moss that still echoes through the years…

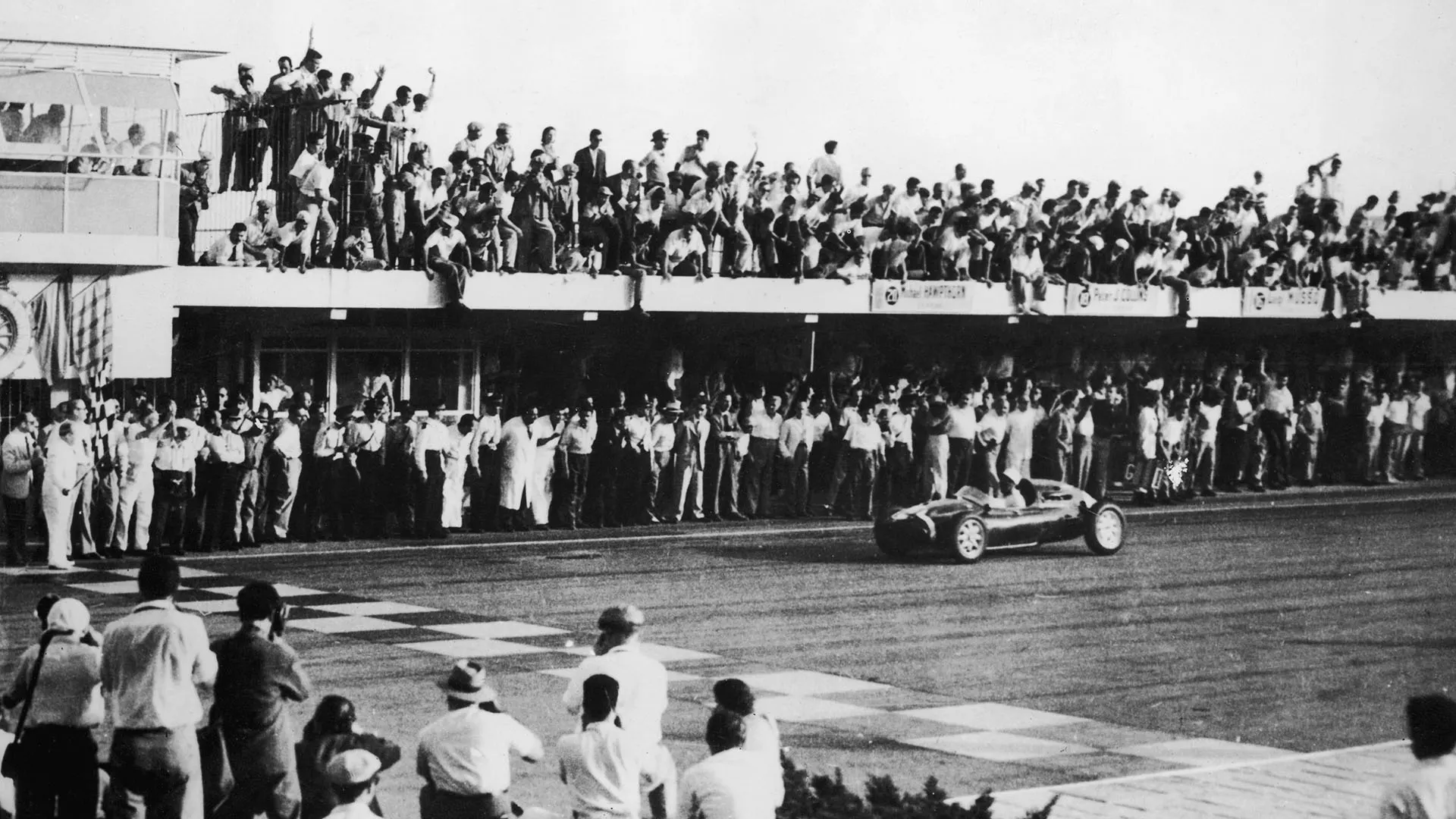

One of the most significant Grand Prix victories in the sport’s history – Stirling Moss in a Cooper-Climax at Argentina 1958 – was based upon a strategy bluff.

Moss taking his mid-engined uprated F2 car to victory over the more powerful but front-engined cars of Ferrari and Maserati was a result that reverberated through the sport and pointed the way to the future. The mid-engined format of car had so many intrinsic advantages over the traditional front-engined machines that it can now be seen as inevitable that this was the way that F1 design would progress.

READ MORE: How Ferrari stole victory from Renault with a secret 4-stop plan

But actually, on the day, that victory was won by the strategy gamble that Moss and his mechanic Alf Francis had devised. It was only later understood that such a strategy was only made possible by one of the main advantages inherent to a mid-engined car – that of light weight.

This enabled Moss to run through the race non-stop on the same set of Dunlop tyres while the rest of the field, in the heavier front-engined cars, all planned their races around a mid-race tyre change and refuel. The winning trick of Moss, aside from a brilliantly judged personal performance behind the wheel, was to keep the non-stop strategy a secret.

Privateer entrant Rob Walker owned the Cooper, which was an adapted F2 car with an engine enlarged to 2-litres, but still giving away half a litre and around 80 horsepower to the traditional front-engined Ferrari Dinos and Maserati 250Fs. But what that mid-engined layout did allow, quite aside from better dynamics based around a more favourable weight distribution, was a massive weight-saving over the traditional Italian cars.

Consisting of little more than a few tubes with an engine and gearbox at the back, it weighed in at just 360kg (there was no minimum weight requirement at the time). The vastly bigger front-engined cars were around 220kg heavier. This actually gave the Cooper a superior power-to-weight ratio – though this wasn’t evident in qualifying as Moss lapped only seventh-fastest, almost 2s slower than the pole-sitting Maserati of the Maestro, five-time world champion Juan Manuel Fangio.

It would only have reinforced the widespread opinion that this tiny mongrel of a car would be no match for the thoroughbreds.

Perhaps Moss’ low-key qualifying performance was all part of the ruse, or maybe it was just a reflection of the last-minute nature of the Cooper’s entry into the race.

The Ferraris and Maseratis had been there for some time already, practising, as the organisers frantically tried to find a way of getting Moss – by then a major star – into their race, given that his contracted team, Vanwall, were not taking part because they had not yet adapted their engines to the pump fuel newly demanded by the ’58 regulations, F1 cars having previously run on an alcohol-based brew.

It was Moss who had the idea of asking Walker if he could use his converted Cooper. Walker didn’t make the trip himself but agreed to send the car and his mechanic Alf Francis. It was air-freighted in order to be there in time – at the cost of the organisers.

READ MORE: F1’s Best Drives – Moss withstands the might of Ferrari at the Nurburgring

Even if Moss did suspect that actually the Cooper just might be fast enough to win this race on merit, he and Francis knew their chances would be doomed if they had to make the same mid-race pit stop for fuel and tyres as everyone else. Each of the Cooper’s wheels were secured by four bolts, the car having been configured for the shorter F2 races where pit stops didn’t feature. With only Francis on hand to change them, a pit stop would have taken between two to three minutes.

The pukka F1 cars of Ferrari and Maserati had single quick-release central spinners securing each of their wheels, and with a full crew could be turned around and in less than a minute.

Moss made a point of publicly dismissing his chances because of how much time he was bound to lose in the pits. But he had no intention of making a pit stop. Instead, he had Francis fuel up the car for the full distance.

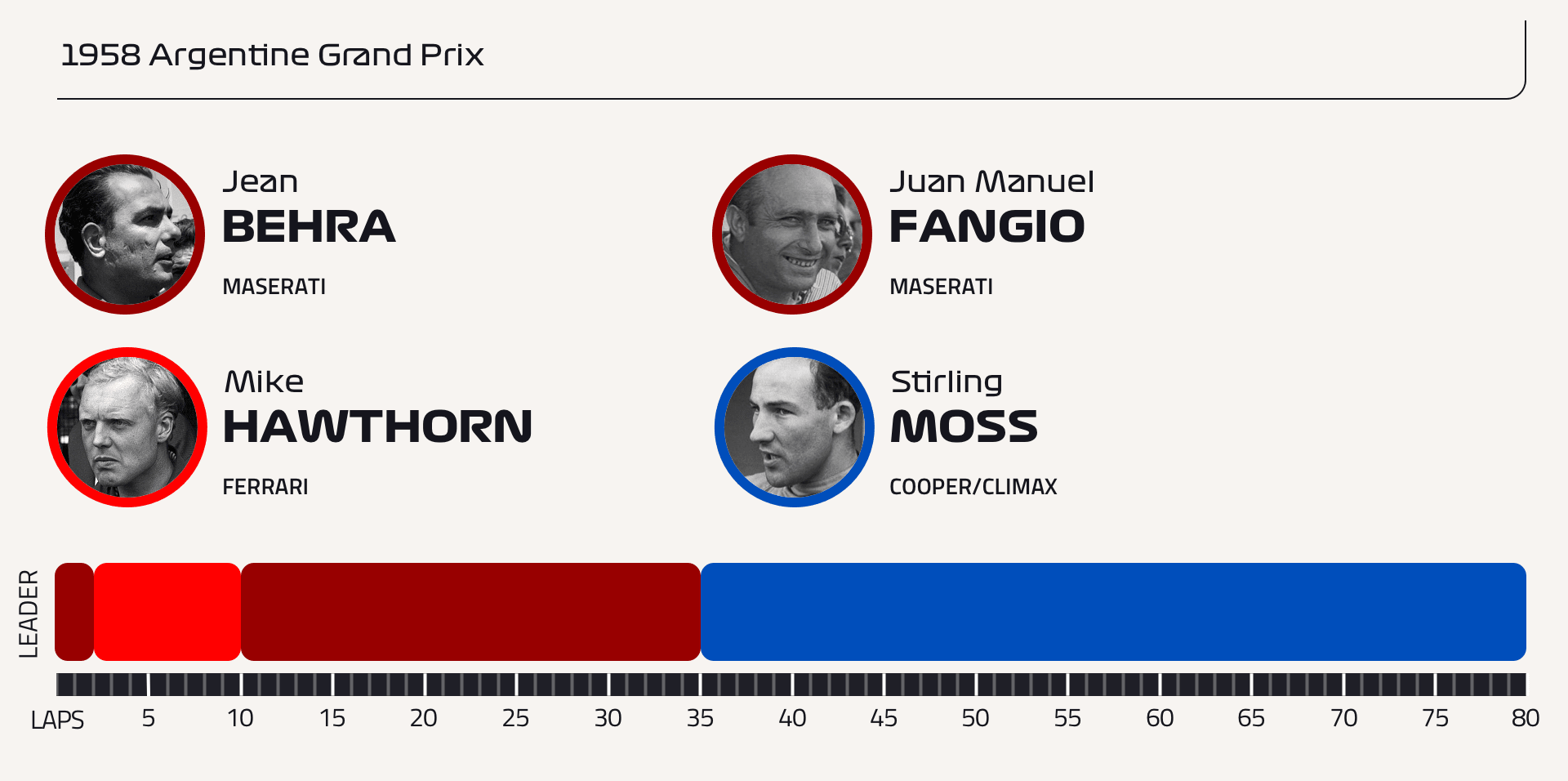

Moss took the early stages easy in the fuel-heavy car, running in fifth place as local hero and reigning world champion Fangio quickly picked off early leaders Jean Behra (Maserati) and Mike Hawthorn (Ferrari) and proceeded to pull out a big lead. Peter Collins’ Ferrari broke its driveshaft at the start, so that was one key rival out of the way.

READ MORE: The greatest of all time? Discover Fangio's Hall of Fame profile

As the Cooper’s fuel load came down, Moss was able to pass the Ferrari of Luigi Musso for fourth. Hawthorn pitted with low oil pressure and although he re-joined, this had promoted Moss to third. Behra spun on the slippery track surface as his original tyres wore out, putting Moss a distant second.

On the 35th lap, one of Fangio’s tyres threw a tread and he lost an age limping back to the pits, where the tyres were changed and the car refuelled. He rejoined a long way behind in fourth, and every time he extended the engine trying to make up for the lost time, it would begin overheating, this a consequence of it having been designed around the superior cooling properties of the previous alcohol-based fuels.

Musso, Behra and Hawthorn all made their planned stops for new tyres. Musso assumed the chase of the yet-to-pit Moss, but a long way distant. Moss continued to lap at quite a gentle pace as he desperately tried to eke-out the tyre life. Musso, expecting Moss to pit, didn’t initially push to try to make up the deficit. In the pits, Francis kept the subterfuge going by hanging out a tyre over the pitwall each time Moss passed. Moss would give a wave of acknowledgement, but carry on.

With 14 laps to go, Moss could see in his mirrors that a strip of white canvas was becoming visible beneath the rear tyre treads. He was even using the grass on some corners in an effort to try and cool them. By now the Ferrari pits began to realise what the game was – and gave Musso urgent encouragement from the pit wall to hurry up. It took a time for Musso to understand what they were trying to convey and by the time he did so and began to press on, it was too late. He crossed the line 2.7s behind the victorious Moss.

The front-engined cars would dominate for a little longer. But a new era of F1 was underway.

Next Up

Related Articles

Who are the reserve drivers for each F1 team in 2026?

Who are the reserve drivers for each F1 team in 2026?.webp) ExclusiveDrive to Survive’s producers on how Season 8 came together

ExclusiveDrive to Survive’s producers on how Season 8 came together F2 champion Pourchaire joins Mercedes as Development Driver

F2 champion Pourchaire joins Mercedes as Development Driver How Drive to Survive changed fandom and racing culture

How Drive to Survive changed fandom and racing culture.webp) UnlockedWhat's happening at Aston Martin?

UnlockedWhat's happening at Aston Martin? BettingF1 betting talking points ahead of 2026 season

BettingF1 betting talking points ahead of 2026 season