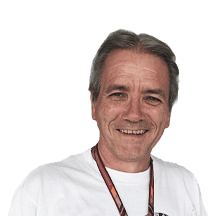

Brazil’s lost champion? David Tremayne on Carlos Pace, the racer after whom the Sao Paulo circuit is named

Coming just 13 days after the fatal accident that befell Tom Pryce in the South African Grand Prix on March 5th, 1977, Jose Carlos Pace’s death in a plane crash stunned the F1 fraternity.

Handsome and quick, he was the archetypal Brazilian racing driver who followed his trailblazing friends Emerson and Wilson Fittipaldi to Europe. On his day he had the speed and race craft to beat anyone, and had proved it convincingly at the autodromo in Interlagos that would later be named in his honour when he won the Brazilian GP two years earlier.

Next Up

Related Articles

/16x9%20single%20image%20-%202026-02-18T145304.510.webp) FIA issue statements on commission and power unit meetings

FIA issue statements on commission and power unit meetings Who's driving on Day 1 of the second test in Bahrain

Who's driving on Day 1 of the second test in Bahrain BettingWhat could move the markets in the second Bahrain test?

BettingWhat could move the markets in the second Bahrain test? What we learned from Day 1 of the second Bahrain test

What we learned from Day 1 of the second Bahrain test/16x9%20single%20image%20-%202026-02-19T183139.714.webp) Lowdon warns not to ‘read too much’ into Cadillac issues

Lowdon warns not to ‘read too much’ into Cadillac issues/16x9%20single%20image%20-%202026-02-18T155544.362.webp) Russell tops Day 1 of second Bahrain test

Russell tops Day 1 of second Bahrain test