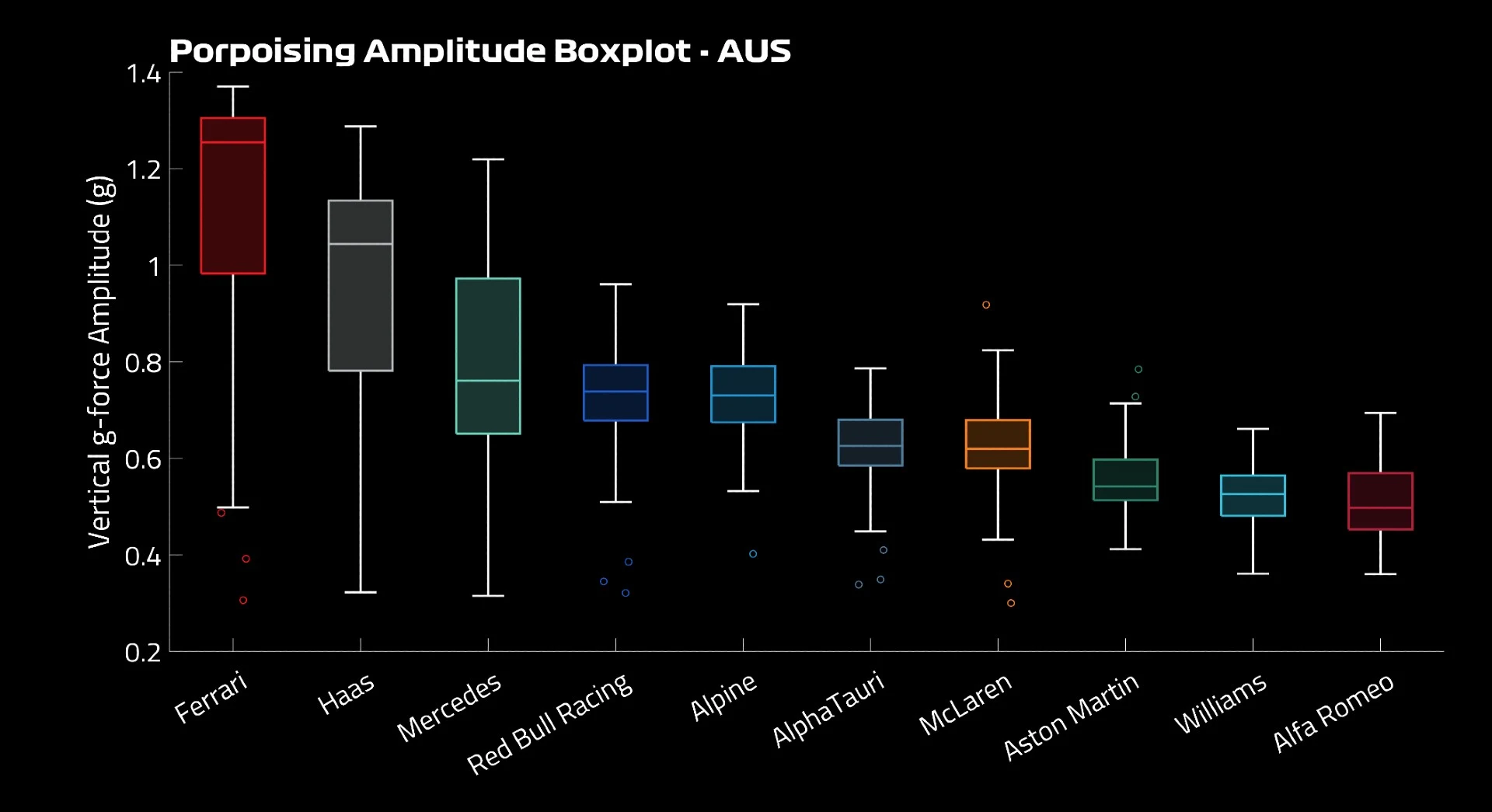

As Mercedes continue to struggle with their porpoising issues, leaving Ferrari and Red Bull to fight it out at the front of the races, there is some mystification about why the Mercedes W13 should be up to one second slower than the Ferrari F1-75, even though the latter exhibits fairly severe porpoising too.

At Albert Park, at the end of the straight before the fast chicane of Turn 9, the Ferrari’s bouncing looked every bit as bad as that of the Mercedes. Yet Charles Leclerc won the race from pole for the Scuderia in dominant fashion.

First, we should clarify that aerodynamic porpoising is induced by downforce – and that downforce is the key to lap time. Lando Norris – whose McLaren is relatively immune from porpoising but also lacking in downforce – put it like this: “We don’t have much porpoising. But porpoising is not necessarily a bad thing. For some cars they are gaining performance from the thing which causes the porpoising.”

Norris would surely surrender his smooth ride in exchange for lap time.

But the important distinction between the porpoising of the Mercedes and that of the Ferrari is that on the Mercedes, it is triggered at lower speeds than on the Ferrari. If this coincides with speeds at which any of the corners are taken, then the team will need to increase the ride height.

This will move the porpoising trigger point to a higher speed, allowing the corners to be bounce-free, but in the process it reduces downforce. It imposes a natural limit on the amount of downforce the car can tolerate.

READ MORE: Russell says first Mercedes podium and second-place in the championship is ‘pretty crazy’

On the Ferrari, the porpoising is clearly only being triggered at speeds beyond which the fastest corners are taken. Even the high-speed porpoising at the end of the straights could be eliminated but it would mean less downforce available for the corners (and braking).

Leclerc talked a little about it in Australia: “We need to tackle it because it can affect consistency. But it’s not like I could have gone faster if it wasn’t for the bouncing. The only time it was a factor was on the restarts I wasn’t confident I could brake extremely hard for Turn 1 on the restart because of the bouncing. But otherwise it was OK.”

Mercedes’ problem is not the bouncing per se, but the amount of downforce they have to surrender to keep it from doing it in the corners.

From there, looking into why that might be, we must move into technical conjecture. It has been pointed out that the four cars with the Mercedes power unit – Mercedes, McLaren, Aston Martin and Williams – are all struggling for pace. Mercedes are around 1s off Ferrari. McLaren a further 0.5s adrift (on average) than that and trailing a couple of tenths behind Alpine. Aston Martin and Williams are the slowest of all.

But we know from GPS analysis that although the Mercedes power unit is slightly down on power to the Ferrari, the deficit accounts only for around 0.15s of lap time. Given that even Mercedes are 1s off the pace, the power unit cannot possibly be the main culprit for the performance shortfall of any of these teams.

If we confine our study just to the three teams which use the Mercedes PU and gearbox (i.e. excluding McLaren), then we also see a correlation with that and the severity of the porpoising issue.

Correlation and causation are not necessarily the same but both Aston Martin and Williams know they could unleash a big chunk of performance, if only they were not having to raise the car away from the porpoising threshold.

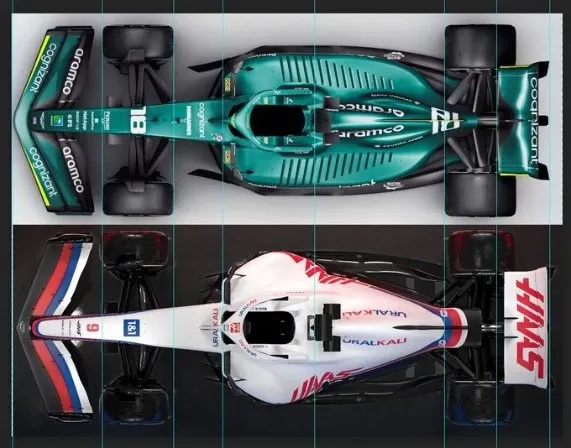

Why would a gearbox cause such an issue? The length of the gearbox casing is a reflection of how a team chooses to package the mechanical components of its car. If we look at the Mercedes, Williams and Aston, we can see that the sidepods and floor intake begin further back than on other cars. This maximises the distance between the front wheels and the sidepods, which is traditionally aerodynamically beneficial.

HIGHLIGHTS: Watch the action from a thrilling 2022 Australian Grand Prix

But to keep the car within the regulation wheelbase limit, this rearward-biased packaging of the radiators and associated apparatus means a short gearbox casing. If we look at the Ferrari and Haas (which share a PU and gearbox) we see that the sidepods are further forward and that much of the cooling apparatus is pushed up towards the front, giving a big, bluff front to the sidepods but allowing the rear bodywork to cut in more extensively.

Looked at from above, it is much more teardrop in shape than the Mercedes, Williams or Aston Martin (below).

The Red Bull and AlphaTauri are configured much more like the Ferrari, in this regard, than the Mercedes. As the sidepod volume begins and ends sooner, so the wheelbase is then defined by a longer gearbox casing.

What might this have to do with porpoising? There are at least two possibilities:

-

The wider bodywork at the rear may be contributing towards the airflow restriction of the underbody. The more teardrop-shaped upper bodyworks of the others should be able to exert a more helpful airflow over the top of the diffuser, potentially making the underbody tunnels more stall-resistant.

-

Where the stall point is relative to the car’s centre of gravity could affect the severity of the bouncing. The short gearbox layout could be putting that centre of gravity at a really awkward point relative to the stall point of the underbody and inducing a leverage effect.

We should emphasise that none of this is anything other than conjecture and that the answers may in reality be very different. But there is something nagging about the correlation between the three cars using the same layout, and the severity of their bouncing problem.

Tap here to find out more about F1 TV, including enhanced race coverage, exclusive shows, archive video and more.

Next Up

Related Articles

/16x9%20single%20image%20-%202026-02-19T183139.714.webp) Lowdon warns not to ‘read too much’ into Cadillac issues

Lowdon warns not to ‘read too much’ into Cadillac issues HighlightsCatch the action from Day 2 of the second Bahrain test

HighlightsCatch the action from Day 2 of the second Bahrain test Watch as F1 TV break down Day 1 of second Bahrain test

Watch as F1 TV break down Day 1 of second Bahrain test What we learned from Day 1 of the second Bahrain test

What we learned from Day 1 of the second Bahrain test/16x9%20single%20image%20-%202026-02-19T105547.998.webp) Norris leads on second morning of final Bahrain test

Norris leads on second morning of final Bahrain test/16x9%20single%20image%20-%202026-02-20T181924.153.webp) What we learned from Day 3 of the second Bahrain test

What we learned from Day 3 of the second Bahrain test