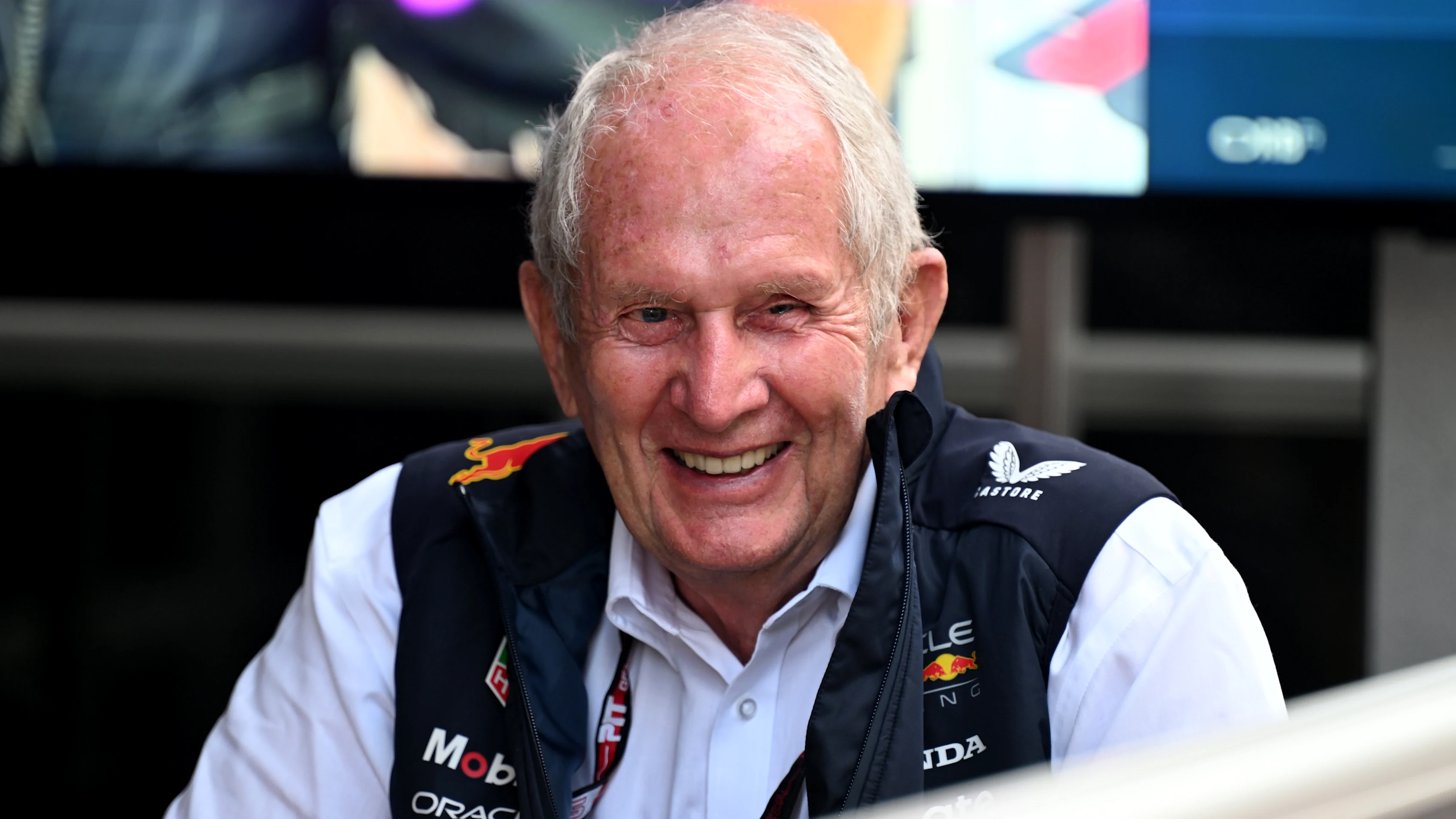

TREMAYNE: Why I’ll miss ‘true racer’ Marko as he bows out of Red Bull

As Helmut Marko retires, another precious link with F1’s glorious past is gone, says David Tremayne…

To many people in the paddock these days, I suspect the 82-year-old Austrian Helmut Marko was probably just ‘that crotchety old guy at Red Bull who always says exactly what he's thinking.’ Most were probably wary of approaching him.

I’m happy to say I loved and respected him. And as I said to Mark Webber’s partner Ann Neal, back in the Multi-21 days when she suggested that he “couldn’t do” some of the things he was doing, you had to know Helmut and his background first before you could truly understand him.

If you believed everything you heard about him, you'd think he was a tyrant, a bully who had no qualms about smashing young drivers’ careers without a second thought if they failed to get the job done. But he was raised in the school of hard knocks, where you stood for yourself.

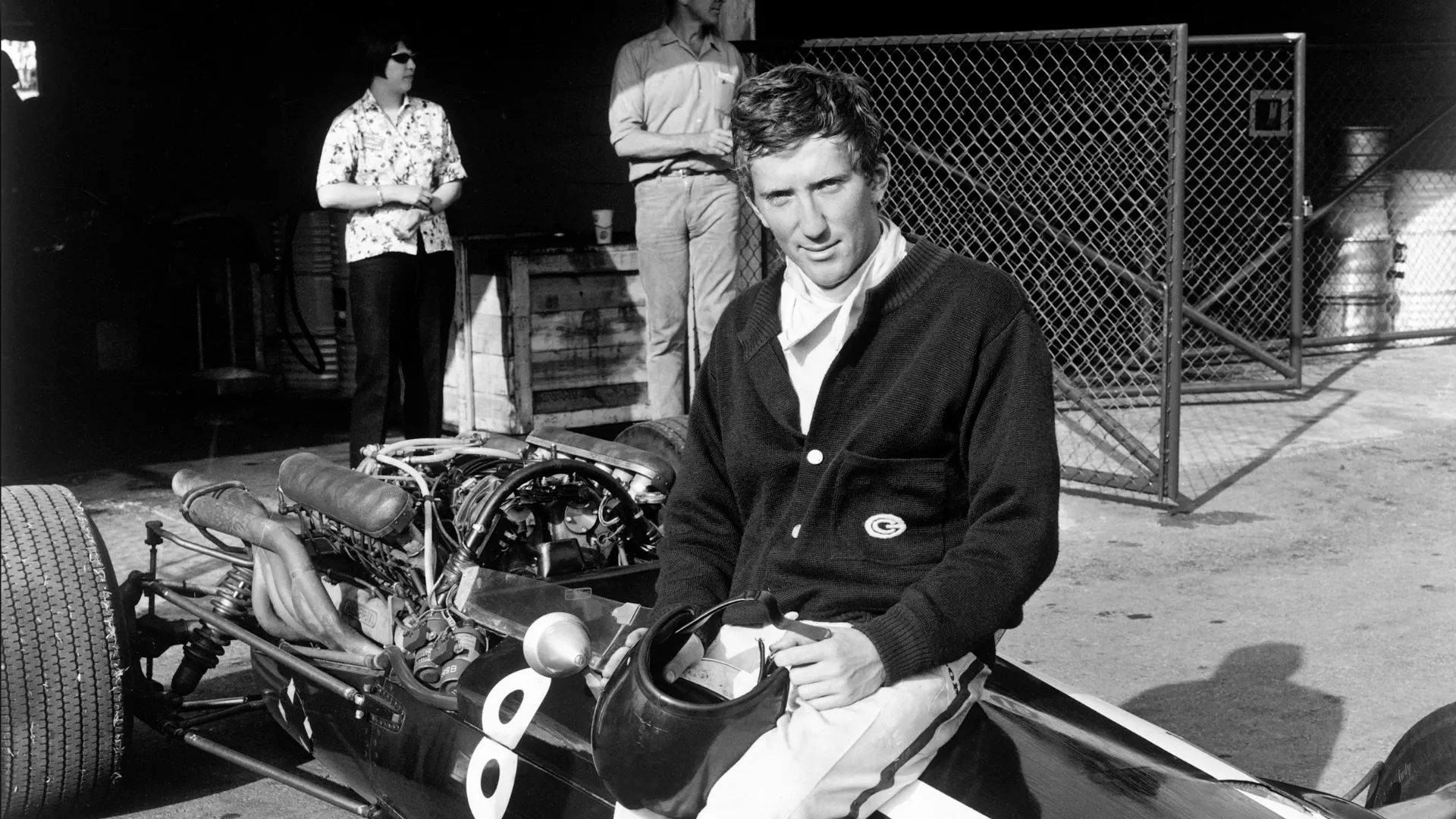

He and Jochen Rindt, who would become the sport’s only posthumous World Champion in 1970, were good buddies. Each had that wanton wildness during their school days that would prove sound preparation for the racing world that awaited them, but accelerated their expulsion from the Pestalozzi School in Graz.

“Let’s put it this way,” Helmut once explained of his removal from the school with a chuckle. “If we left, they would give us a positive report. If not, we wouldn’t make it. So it was a very attractive offer. We messed about, we skipped lessons. We were a wild age and we really didn’t fit in this system of nice boys.

“So then we went to a boarding school called Bad Aussee, in the mountains, and that was a really wild time because whatever you had to do, you had to organise yourself. Climbing out of the windows during the night…”

First they raced each other on their ‘wombats’ (mopeds), later in cars, on the roads around Graz. The deal was that each would drive whichever car was available, until they made a mistake, whereupon they would be replaced. If there was more than one car, the deal was that if you stuffed it, you were on your own. Helmut once spun his father’s Chevrolet, ‘borrowed’ without paternal permission, down a hill. Get out of that! Thus, the young electrical dealer’s son was used to fending for himself.

It's largely overlooked now, but he was a damn good driver himself, and after Jochen’s death at Monza in September 1970 he focused on his own career. He was a topline European 2-litre sportscar racer in a Lola T212, as Brian Redman will attest, and won Le Mans in 1971 in a Martini Porsche 917K with co-driver Gijs van Lennep.

He got his first chance in F1 with BRM in 1971. The team was a shambles as Louis Stanley sought to run five cars, and it wasn’t until 1972, and the French GP at Clermont Ferrand, that Helmut finally got a halfway decent P160B instead of an old nail P153.

He qualified it sixth on this mini-Nurburgring, and was dicing for fourth with Ronnie Peterson in a March 721G and champion-elect Emerson Fittipaldi in a Lotus 72, the leading BRM driver by a country mile. The track was littered with stones, and one was thrown up from one of their wheels, went through his visor like a bullet, and struck him straight in the eye.

He was the man who could have been Niki Lauda before Niki Lauda. But in that moment his racing career ended.

“It was all coming together,” he remembered. “And funnily enough I had just got some autographs to sign and there were photos of me in my 153 and one in the 160. In the 153 I was sitting properly, in the 160 I remember that it came late – like it always did with BRM! – and I was sitting about 10cm higher. They couldn’t adjust the seat properly for the race. If I would have been in my normal seating position, nothing would have happened.

“I didn’t know immediately that I was in trouble. I saw something coming. I just remembered I was sixth and we had 258 litres of fuel and there were 18 cars behind me, so if I don’t do something smart, they could hit me. I managed to raise my arm and park the car, fortunately for me and the others.

“I was for two months in hospital and I had stitches in my injured eye and I couldn’t see because I had covers on both eyes. Then you are thinking a lot. At one stage I said, ‘That’s it!’ I was 29, the victim of an accident… One night it was clear that it wouldn’t be the same as it was before… But life goes forward, and I had to cope with that.

“Of course I was bitter in the beginning. It was, ‘Oh, by Christ,’ but being in the hospital you see or you hear what is going on around you, so then you relatively see that it is not so serious. You have to get normal again, and stay grounded.”

Years later, I was speaking to him about his protégé Helmuth Koinigg, who would lose his life in the 1974 US GP. Helmut said Koinigg’s Formula Vee sponsor wanted the pair of them to do a hillclimb. Helmut told Little Helmuth he would only do it if he could have a specific car, the one that his protégé wanted – because it was quicker. Of course, Big Helmut prevailed and duly won. And then he told me the most extraordinary story.

Heading home he read in a newspaper of the crash of scheduled Alitalia flight 112 when the airline’s Douglas DC-8-43, flying from the Leonardo da Vinci Airport in Rome to Palermo International Airport, flew into Sicily’s Mount Longa. In Italy’s biggest single aircraft disaster, all 108 passengers and seven crew were killed.

“If I hadn’t done that hillclimb I would have been on that flight, heading out to test for Alfa Romeo for the Targa Florio,” he said nonchalantly as we sat outside one of the attractive little hospitality units in the paddock in China.

“Man, I’ve never seen that written anywhere!” I exclaimed.

“That’s because I never told anyone,” Helmut said, as if it was no big deal.

Imagine… That had occurred on May 5. He would have been entitled to feel that the gods were smiling upon him. Then, in a flash on July 2, that stone took his eye and his career was over… Such cruel fortune…

He took up running his own hotel, and then ventured back into racing by setting up his own Formula 3000 team. Along the way he worked with another doomed young Austrian, Markus Hottinger, who was killed in a Formula 2 race at Hockenheim in 1980.

“There was this thing with the Austrians, that they had such odd accidents,” he recalled quietly. “With Jochen it was under braking and the nose wedged beneath the guardrail at Monza and it was torn off and he was pulled out of the car. Two metres earlier or later...

"Fortunately I was not at Watkins Glen when Helmuth was killed. That was a big shock. He had a puncture and went under the guardrail, and was decapitated. And with Hottinger, a wheel from Derek Warwick’s car was bouncing around and it hit his head…

“Both Helmuth and Markus gave something to racing… And, yes, both of them could have made it.” He paused for a moment in his reflection, then said, as he had with his own incident, “But life goes on…”

So that all goes a long way to explaining why he has left the racing battlefield strewn with the careers of the myriad drivers who failed to go all the way through Red Bull’s youth programme: Tonio Liuzzi; Patrick Friesacher; Sebastian Bourdais; Scott Speed; Sebastien Buemi; Jaime Alguersuari; Lewis Williamson; Christian Klien; Pierre Gasly; Alex Albon; Sergio Perez; Liam Lawson; Yuki Tsunoda.

With his famed, Lauda-matching Austrian pragmatism, he has always sought the best, looked for those drivers prepared to go the extra mile to succeed. He’s never been one to wrap an avuncular arm around a struggling racer. And he found what he was looking for with Sebastian Vettel and, later Max Verstappen.

He admits cheerfully that back in the dark days after his career ended in 1972, he never dreamed he would get a second chance in Formula 1. “No, not at all. But the chance came fortunately through Red Bull with the Jaguar team.”

He and the great Dietrich Mateschitz knew one another in Styria long before their collaboration at Red Bull began. “I was the one who said Christian [Horner] is our man, and I’m glad I did,” he said a few years ago, before the death of Mateschitz and Horner's departure from the team earlier this year.

“In the beginning, a lot of experts said it couldn’t work, but he’s proved that he’s capable. I saw how he was running his F3000 team; we were young and we were different, and we made the old-established people see differently. It made sense. Here, it’s very open, and we don’t tell stories. We just try to find the best solution for the team, and we do it without any egos.

“I don’t handle the daily operations. That rests with Christian. If it’s a major decision, either I decide or else if necessary I take it to Didi [Mateschitz].”

Christian didn’t always agree with Helmut’s version of how they worked together, but the fact is that the old warrior played a key role in forming the team, and together they would take it to such fantastic success.

As of today, Red Bull Racing have won 130 Grands Prix, eight Drivers’ and six Constructors’ World Championships, toppling the likes of Ferrari and Mercedes along the way.

Sadly, it now looks like it is time for him to saddle up. Times change, but it makes me sad. No matter what you thought about the way he operated, Helmut Marko was a true racer on and off the track, with the scars to prove it, a great sense of humour and a refreshing penchant for saying exactly what he thought. He leaves a significant, often overlooked legacy, and I for one will miss his huge presence in the paddock.

%20(2).webp)

Next Up

Related Articles

.webp) ExclusiveDrive to Survive’s producers on how Season 8 came together

ExclusiveDrive to Survive’s producers on how Season 8 came together What do the new lights on F1 cars mean?

What do the new lights on F1 cars mean? BettingHow to take a break from gambling when you need it

BettingHow to take a break from gambling when you need it Button tips Hamilton to be 'back to his best' in 2026

Button tips Hamilton to be 'back to his best' in 2026 Perez and Albon offer Hadjar advice on second Red Bull seat

Perez and Albon offer Hadjar advice on second Red Bull seat UnlockedThe key qualities a driver needs in a race engineer

UnlockedThe key qualities a driver needs in a race engineer