The tyre war between Goodyear and Michelin at the start of the 1980s provides the backdrop for another strategic masterstroke from the annals of F1. Mark Hughes recounts the story of the 1981 French Grand Prix, and how Renault’s Alain Prost made use of a race stoppage to take an unlikely maiden win.

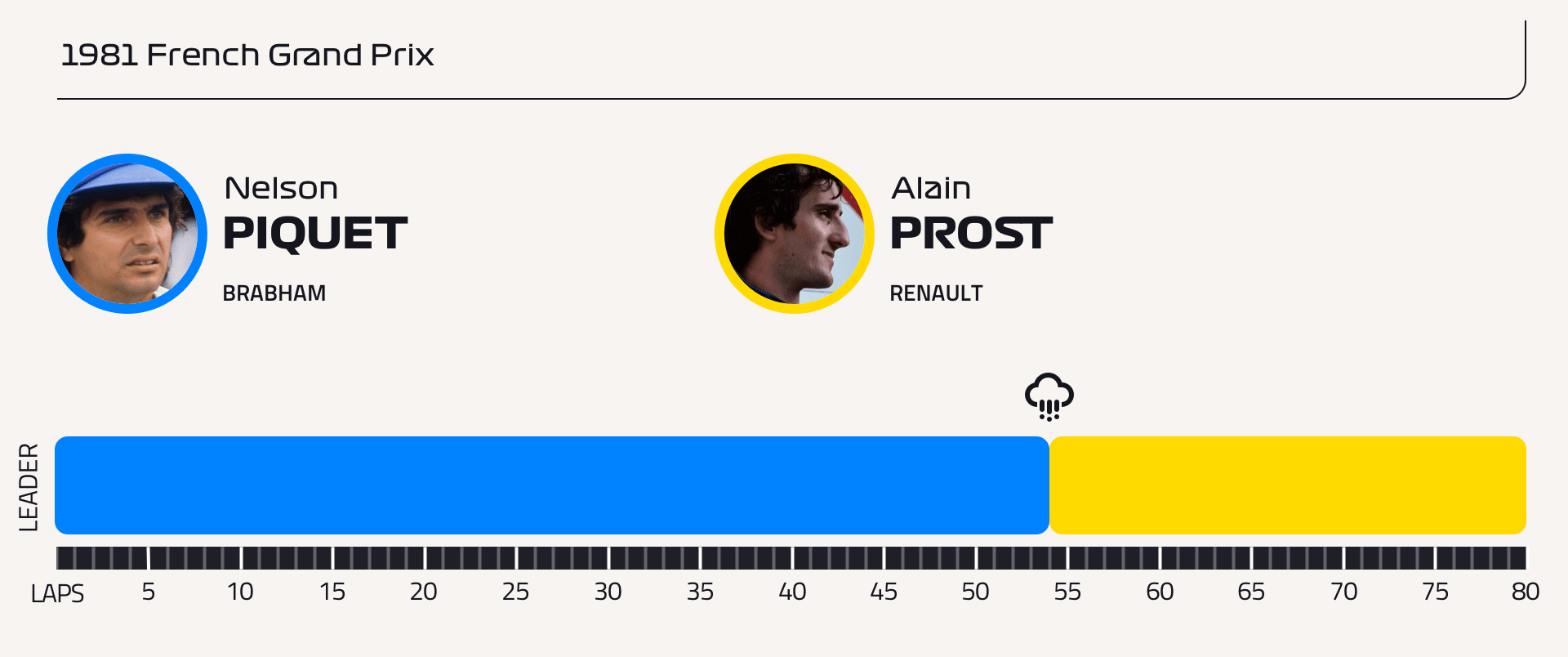

The first of Alain Prost’s 51 Grand Prix victories came in 1981 – and appropriately it was at his home French Grand Prix at the wheel of a French Renault. But what is largely forgotten in the mists of time is that it wasn’t a straightforward dominant run to the flag, but a victory stolen in the late stages from the Brabham of Nelson Piquet.

STRATEGIC MASTERSTROKES: Moss bluffs his way to victory at Argentina in 1958 – and ushers in new era

This came from an inspired tactical choice after the race was run in two parts because of a sudden thunderstorm which caused it to be red-flagged just one-lap short of the 75% distance at which it could have been called and still allocated full points. Essentially, because of the range of Michelin tyre compounds available to them, Renault were able to pull a fast one on the Goodyear-shod Brabham team in the very short re-started phase of the race. It was the sort of quick, flexible thinking that usually marked out the specialist independent teams against Renault at the time – and this was the perfect occasion on which to turn the tables.

The background to the story was a very political one. This was at the time of the FISA/FOCA war for control of the sport. The Bernie Ecclestone/Max Mosley-led FOCA group, comprising mainly the British teams that accounted for about 70% of the grid, were in deep disagreement with FIA President Jean-Marie Balestre about his banning of the side skirts that were a crucial part of generating ground effect downforce from the sidepods.

FOCA had even threatened to break away and form its own series for 1981, the World Professional Drivers’ Championship, and had gone as far as staging a race at Kyalami, South Africa. Aligned on the governing body’s side were Renault, Ferrari, Alfa Romeo and the small Italian Osella team. The South African race had the effect of calling Balestre’s bluff on the threat of the breakaway series and an uneasy compromise was reached between the two warring sides.

But the uncertainty over the winter about what was happening and whether the original FIA-sanctioned World Championship, inaugurated in 1950, was coming to an end caused Goodyear – one of the two main tyre suppliers – to announce their withdrawal from the sport. Furthermore, they were facing budget pressure and were highly dissatisfied with having to supply and service almost all of the field at a time when their rivals Michelin were able to work with just two top teams, Renault and Ferrari.

ALTERNATIVE HISTORIES: What if Hamilton hadn’t joined Mercedes?

Only when Michelin then agreed to fill the void left by Goodyear was the ’81 season even able to get underway at all! But with Michelin now carrying the burden of supplying the field, Goodyear made a shock mid-season return – with the top two FOCA teams, Brabham (Bernie Ecclestone’s team) and Williams. Goodyear had neatly switched the cost of supplying most of the field onto their rivals, allowing them to concentrate their budget on development with two top teams, the very situation that Michelin had previously enjoyed. Ecclestone had played a key role in convincing Goodyear to come back, not only for competitive reasons but because a separate tyre supplier meant FISA had less hold over FOCA as their battle rumbled on.

This is all highly relevant to what played out on that July afternoon in Dijon. The French race marked Goodyear’s return. But it did so with a very conservative range of four compounds, from the hardest ‘A’ through to the softest ‘D’. Goodyear were adamant they would no longer be running to the expense of qualifying tyres that would be thrown away after one or two flying laps. So even the softest Goodyear tyre brought to Dijon was capable of doing a full race distance. This was the season before Brabham re-introduced the mid-race pit stop to F1 and in ’81 the convention was still that Grands Prix ran non-stop on a single set of tyres for each car.

READ MORE: 5 fantastic documentaries to watch on F1 TV

The Goodyear D compound was so robust that neither Brabham nor Williams bothered with the harder, slower A, B or C as it was clear Goodyear on their return had pitched the compounds rather too hard. The D was, however, a very fast race tyre – faster than anything in Michelin’s armoury. Michelin were able to supply their much softer 307 tyre for qualifying, enabling Renault’s Rene Arnoux to qualify on pole in the turbocharged Renault ahead of John Watson in the radical new carbon fibre McLaren MP4/1 – and the second Renault of Prost, all shod with Michelins.

The 307 wasn’t a radically soft qualifying tyre. But it was a qualifying tyre. It could do a few laps, but certainly not a race distance, which at Dijon was set for 80 laps. With no Goodyear to compete against, Michelin had moved away from the super-sticky single-lap rubber.

For the race, Michelin had a much more robust, but slower, tyre that was no match for the Goodyear D. The fact that Piquet qualified his Brabham BT49 fourth-fastest on the much harder Goodyear, of a compound capable of going the full distance, suggested he was actually the race favourite. Everything seemed poised for a triumphant Goodyear return.

The skies were clear as the cars sat on the grid, but there was a forecast of possible thundery showers. An electrical problem with the start lights caused some confusion as they changed from green to red – and then off. Poleman Arnoux was hesitant – and lost out as others assumed the race was on as soon as the green had showed. From row two, Piquet surged into an immediate lead from Watson and Prost. After a couple of laps Prost was able to find his way past the McLaren – but Piquet was already long gone, pulling away at a pace that Prost couldn’t conjure from his Michelins.

That seemed to be that. Piquet extended his lead to over 10s and just controlled things from there, while Prost and Watson circulated in close company a long way behind. But this was at a time before electronically-controlled, rock solid reliability. Anything could still happen – and sure enough, Piquet began suffering a sticky throttle. He could manage it but as the leaders came to lap other cars, he was having to be very conservative, and this was allowing Prost (and Watson) to begin pulling chunks of time back. Piquet would then pull away again as they got into clear air.

LISTEN: Prost on his amazing career, his unique relationship with Senna and his 80s rivals

Prost then encountered his own problem, with the Renault reluctant to engage fourth gear. He used the turbo motor’s grunt to minimise the problem, but he now had his hands full just fending off Watson, let alone challenging Piquet. But then the see-saw swung again – as it became apparent that the front-left Goodyear of Piquet was beginning to suffer, a line of blistering becoming visible as a dark strip. Had he pushed too hard, too early when the Brabham was still heavy with fuel?

So Prost and Watson once again began to catch Piquet. After a few laps of nursing the tyre through the fast right-hand sweeps, Piquet got the blistering back under control and stabilised the gap to around 7s as the race entered its late stages. But there was one more cloud on Piquet’s horizon – a great big black one. Soon it was hovering over the circuit and on the 59th lap it dropped its massive load onto the track all at once.

It was an extraordinarily violent rain burst and the slick-shod cars were aquaplaning everywhere – causing the race to be red-flagged. This was just one lap short of 75% distance. Had they been able to complete one more lap the race could have been declared with full points. Instead, the race order was backdated to Lap 58 – and the remaining 22 laps would be held as a short sprint, with the overall result the aggregate of times of the two races.

The thunderstorm disappeared as suddenly as it had arrived, and by the time the cars were lined up on the grid in their Lap 58 order, the track was almost completely dry once more. The regulations of the time allowed the cars to be worked on during any break in the race, so the Renault mechanics attended to Prost’s gearbox, although they were uncertain if they had affected a full cure.

READ MORE: How Ferrari stole victory from Renault at France 2004 with a secret 4-stop plan

But what the regulations also allowed was a change of tyres – and here is where Renault and McLaren realised there was a golden opportunity. The super-grippy Michelin 307s! Could they do 22 laps? Possibly yes, assessed the Michelin engineers. If they were careful. They were fitted to both Renaults (with Arnoux starting from fifth) and Watson’s McLaren. Piquet had a scrubbed set of Goodyear Ds fitted.

As the lights changed, Prost and Watson had mases more traction than Piquet and surged immediately to the front. Piquet was even passed by Arnoux. This was perfect for Renault, as Arnoux could keep Piquet back as Prost escaped. This would allow Prost a much better chance of pulling out the 7s gap on Piquet needed for the overall win. Assuming he could do that, all Prost – whose fourth gear was now selecting beautifully – needed to do then was control Watson, who briefly scrabbled into the lead on the opening lap of the restart, but ran wide and was repassed by the Renault.

Prost duly reeled the remaining laps off carefully, doing just enough to keep Watson behind, the McLaren driver similarly constrained by the delicate tyres. Piquet could find no way by Arnoux and fell ever-further back. Complicating his life yet more, he was passed by Didier Pironi’s Ferrari a few laps from the end. As Prost took the flag from Watson to the wild approval of the crowd, Piquet was half-a-minute behind and only fifth across the line, third on combined time.

Renault and Prost together had made an audacious choice, brilliantly exploiting the little present the weather had provided. Prost had a Grand Prix victory under his belt in just his second season of F1. There would be many more.

Next Up

Related Articles

BettingCommon F1 betting and gambling myths debunked

BettingCommon F1 betting and gambling myths debunked How Drive to Survive changed fandom and racing culture

How Drive to Survive changed fandom and racing culture How to stream the 2026 Australian Grand Prix on F1 TV Premium

How to stream the 2026 Australian Grand Prix on F1 TV Premium/EXCLUSIVEINTERVIEW%20FEATURE%20V5%20DISPLAY%20-%20single%20arty%20image%20(FOCUS%20IN%20THE%20MIDDLE).webp) ExclusiveLindblad reflects on his journey to F1 in pictures

ExclusiveLindblad reflects on his journey to F1 in pictures.webp) UnlockedWho is in the mix for best of the rest in 2026?

UnlockedWho is in the mix for best of the rest in 2026?.webp) ExclusiveHow Aston Martin are reacting to their pre-season struggles

ExclusiveHow Aston Martin are reacting to their pre-season struggles