Just as fast and furious as the battle on track, the race to bring car updates and out-develop rivals across the course of the season is often where championships are won and lost…

There’s a wistful look in Nick Chester’s eye when he contemplates the idea of a quiet time in the design cycle of a Formula 1 team. “June,” says Renault’s former Chassis Director, finally. “It used to happen around June. You would have pretty much finished developing the current car, and you were just beginning to think about the next one. Of course, that was 10-15 years ago. Now, you develop the current car until October but you’ll have started work on the next car back in January. The team is flat out. Permanently.”

READ MORE: Why pre-season is as much about shaping drivers as shaping cars

There’s a romantic desire to see championships won purely on the skill of the drivers or the brilliance of the initial technical concept but the reality of F1 is that success requires a third element: the speed at which the team can develop through the season and continually reinvent their car. It’s why F1 factories have become monsters of industrial efficiency, consuming talent and resources at one end and spitting out a never-ending stream of new components at the other. Your top gun driver and genius designer aren’t going anywhere if the factory can’t produce the upgrades in a timely fashion.

If we’ve found something that improves the car, we want to get it to track as quickly as possible

This season, given the fact the regulations are largely the same as last year, the upgrade process is going to be more important than ever. The team that comes out on top at the end of the season isn’t necessarily going to be the one that’s done the best job thus far: it’s going to be the one that does the best job from now on.

Accelerating change

The Spanish Grand Prix in early May has traditionally been the time to see the first big upgrades of the season. While the car that races at the first Grand Prix in Australia in March may be different to the one that tests at Barcelona next week, by the time Formula 1 arrives back in Europe, having had a couple of months to assimilate data from the pre-season tests, the teams are in a position to begin adding performance to their cars. At least, that’s how it used to work. The modern reality is that, while the big upgrades still happen, updates arrive race by race. Sometimes even day by day.

“I think the idea of the major upgrade has become a bit of a myth,” says Chester. “We used to go down the route of a few big updates each season, each one quite discrete. Now, we tend to bring new items to most races. If we’ve found something that improves the car, we want to get it to track as quickly as possible.

READ MORE: The 2020 F1 calendar, pre-season testing details and F1 car launch schedule

Speaking mid-way through 2019 when Renault were locked in a fierce battle for fourth place in the championship with McLaren, Toro Rosso and Racing Point, Chester said: “That this season is a massively tight competition doesn’t really affect the schedule – though it does make it more important than ever to get upgrades on the car as soon as possible. If you were in a position well off the teams in front and well clear of the teams behind, you might consider taking the pressure off, skipping the upgrades for a race and instead you might put a few updates together into a larger package that makes it easier for design and manufacturing at the factory, and that, in turn, might allow you to expend a little bit more effort on the future car. But while the competition is as tight as this, you’ll bang everything through as quickly as you can.”

WATCH: Top 10 F1 Substitute Performances

What constitutes ‘everything’ is a lengthy list. In a recent lecture, McLaren Chief Operating Officer Jonathan Neale estimated that an F1 car consists of 16,000 parts, of which only 10 percent are carried over year on year. Were the number of updates to be averaged out over the life of the car, Neale revealed it would equate to "an engineering change every 20 minutes, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, from the moment we release it to the moment we retire it. It's high-speed research and development". Moreover, Neale argued that the car is in a permanent state of obsolescence – because by the time parts are at a race track, there’s a new generation going into production to replace them.

While Chester and Neale adhere to the theory of constant evolution, incremental change is still sometimes augmented by a larger update, simply because on occasion a sequence of parts needs to go onto the car as one in order to deliver an overall performance gain.

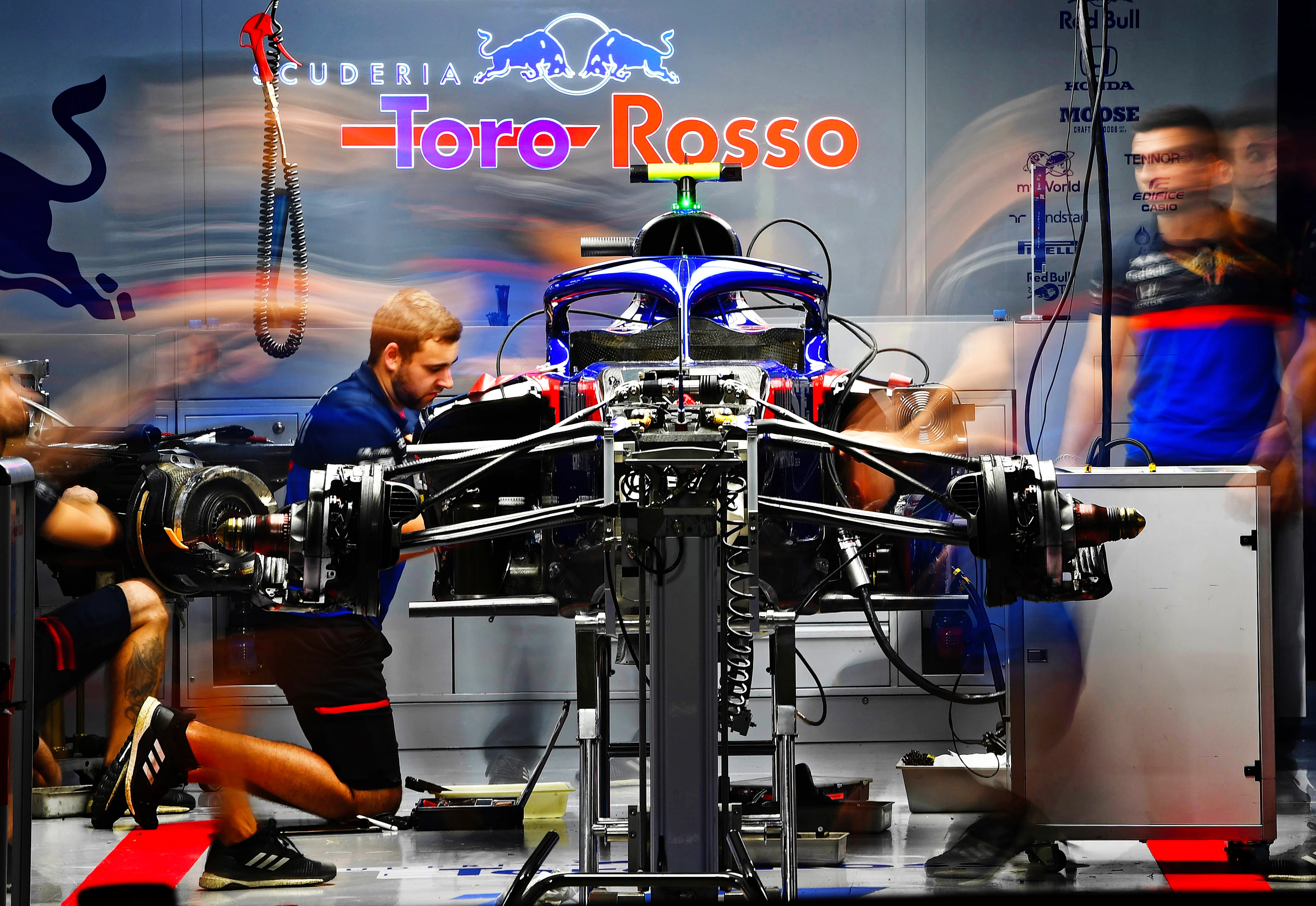

How Toro Rosso tackled 2019

In 2019, Toro Rosso – now AlphaTauri – planned larger updates for Barcelona and Silverstone, to supplement what Technical Director Jody Egginton called ‘rolling development’.

“The major milestones for Toro Rosso will be [Spain and Britain] – but in-between there will be something new at nearly every race,” he said early in 2019. “A key part of our plan for the season has been rolling development. Following the launch, there has been a series of small updates to the floor, the barge boards, the front wing, the brake ducts. Not big changes but lots of them: whenever we find some performance in the wind tunnel we take it to the car.

However good your resources are, you’re always left thinking: ‘if I had a bit more, I could do it quicker'.

“Behind that, there’s another stream of development that deals with bigger changes,” he added. “This will be things we’ve seen in the wind tunnel that look like they’ll bring performance – but they perhaps need to be combined with something else. Those updates will be on and off the wind tunnel model several times before going onto the car as part of a bigger update.” The areas of the car to which Egginton referred were, not coincidentally, those most affected by the 2019 regulation changes. And while upgrades are, to a certain extent, a response to what a team sees on track, and what they see rivals doing, they would have also formulated a plan to best deploy their resources in-season long before a wheel has turned in anger.

“During the design phase, we try to build in as much flexibility as possible,” said Egginton. “Within that, you have a number of streams: you have parts that are evolving, parts that are frozen for the moment and parts that you don’t yet have a clear view on.

READ MORE: Why 2020 will be a defining year for Vettel, Ferrari’s ‘man of the people’

“This tends to be a theoretical plan with a lot of ‘what-if’ scenarios – but you need to have it at a team like Toro Rosso so the guys in the factory know what they’re going to be doing – because we need to make sure the design and manufacturing capabilities line-up. We can’t afford to have 200 people standing around waiting for someone to dream up a new part.”

Hitting diminishing returns

How many times a team can go through the upgrade cycle during the season is limited either by the speed with which parts can be designed, or the pace at which they can be manufactured. Sometimes, says Chester, it can be a mixture of the two.

“It really depends on which parts you’re making,” he says. “For something like a front wing, it’s a team of designers working flat-out on it for four to six weeks after it’s come out of the wind tunnel. Then it goes into production and they’ll be flat-out as well. However good your resources are, you’re always left thinking: ‘if I had a bit more, I could do it quicker'.

“We try to be a little bit careful about not attempting to do too many things at the same time. There’s always the potential to try to juggle too much and not actually get anything to the track for the target race.”

In this, as in every season, there’s a point at which teams – even teams fighting tooth-and-nail for a title or a good final position in the constructors’ championship – will stop attempting to improve their car. They do it because the returns from improving the current car are outweighed by the need to devote time and energy to the next one. With no major technical changes for 2020, upgrades from 2019 continued to come late into the season because any goodness located for the current car was likely to be transferable to the new.

READ MORE: F1 RULES & REGULATIONS: What’s new for 2020?

The elephant in the room, however, is the looming 2021 technical regulation change. “That’s going to be tricky to manage… ” cautioned Chester.

It looks like there isn’t going to be a quiet period for F1's team factories any time soon.

This article originally appeared on F1.com on May 8 2019

Next Up

Related Articles

Honda issue statement amid Aston Martin’s test struggles

Honda issue statement amid Aston Martin’s test struggles See Tsunoda back in a Red Bull at special San Francisco demo

See Tsunoda back in a Red Bull at special San Francisco demo/16x9%20single%20image%20-%202026-02-20T192341.430.webp) In NumbersWho was fastest at the second Bahrain test?

In NumbersWho was fastest at the second Bahrain test? POLL: Who impressed you the most in pre-season testing?

POLL: Who impressed you the most in pre-season testing?/16x9%20single%20image%20-%202026-02-20T181924.153.webp) What we learned from Day 3 of the second Bahrain test

What we learned from Day 3 of the second Bahrain test The top tech innovations from 2026 pre-season testing

The top tech innovations from 2026 pre-season testing