The insider’s guide to… Preparing a car through practice

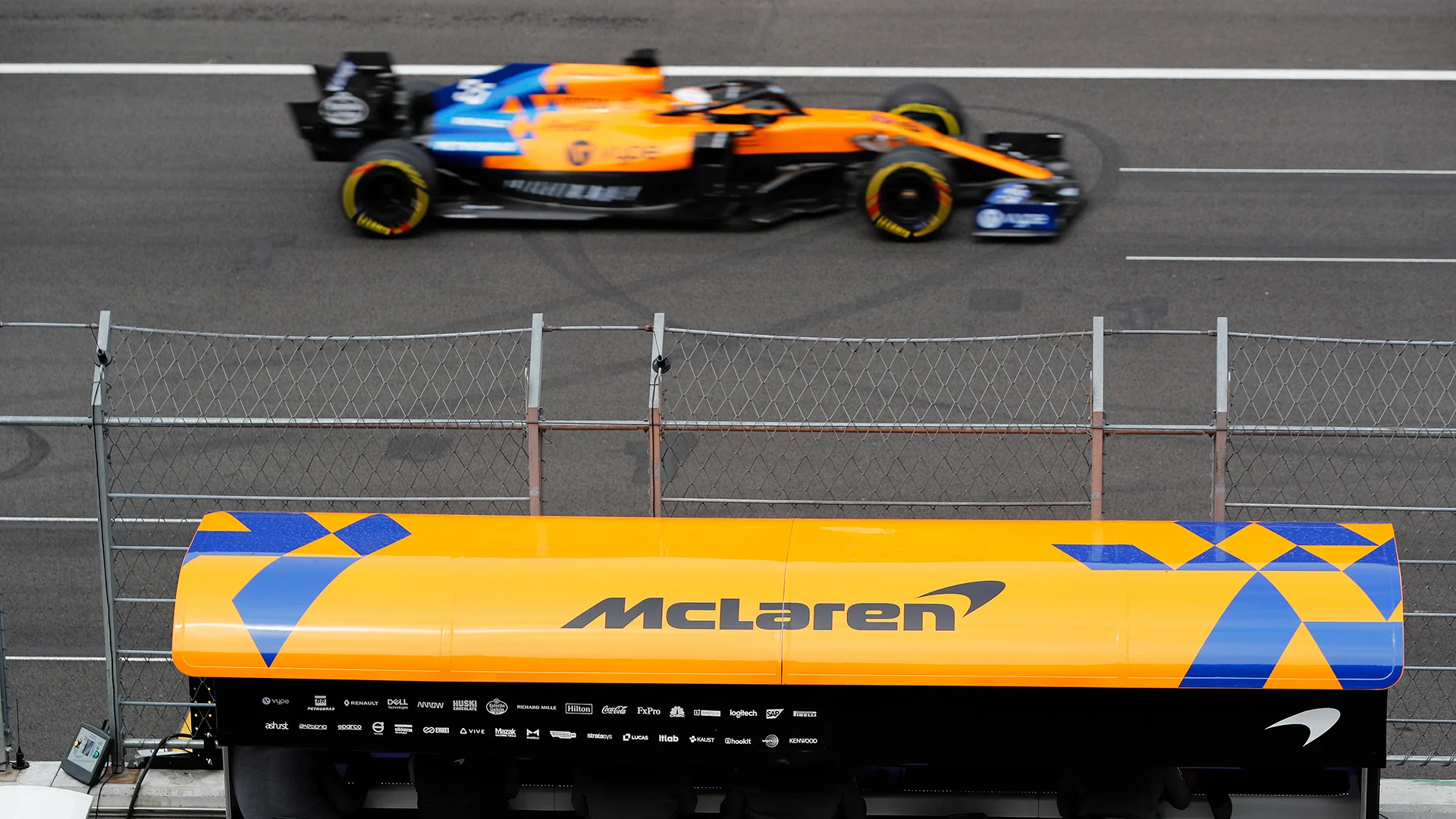

Practice makes perfect: At least that's the idea. Potential is one thing, but extracting performance from an F1 car is another matter altogether. McLaren’s young star Lando Norris and the engineers of Car #4 explain how F1 practice sessions are about a lot more than just practice…

A Formula 1 car never races twice. The relentless pace of improvement, and the ever-changing demands of 22 unique circuits ensure any particular arrangement of bodywork and mechanical underpinnings is ephemeral at best. From race to race the car always changes – but more than this, it also changes session to session.

READ MORE: Norris ‘confident’ McLaren can make another step in 2020

Formula 1’s three practice sessions – two 90-minute periods on a Friday and a final hour on Saturday morning – rarely make the headlines. With attention rightly focused on Saturday qualifying and Sunday’s race, in public perception the four hours of practice serve only as a warm-up act, a chance to watch the drivers in action in a low-pressure environment where time is not of the essence.

For teams and drivers, the three sessions are a lot more intense.

While car performance is developed in the wind tunnel and design office, extracting that performance is the part-art, part-science challenge of Fridays and Saturday mornings.

You can see the significance on the timesheets. Look at a pole position time and then refer back to the first flying lap that car did on its softest tyre compound. Usually it’s a couple of seconds slower and there’s a good chance that the initial time wouldn’t have been good enough to make Q3.

Some of the gain is track evolution (rubber going down in the braking zones, improving grip levels) and some is from engine modes and weight reduction. The rest comes from the process of fine-tuning the car – and also fine-tuning the driver. While a large number of people, both at the track and back at base, contribute to the process, the activity centres on the driver working with a race engineer and a performance engineer – and they start a long time before even setting foot at the circuit.

It’s an over-simplification to say it’s spanners versus electronics – but it’s not far off. It’s more driver-plus-electronics and driver-plus-spanners

THE BASELINE

“It’s a case of deciding before heading to the circuit, how do I make the best car?” says Will Joseph, race engineer for Lando Norris. “Because the regulations are relatively stable at the moment, our starting point will be last year’s car.

“We’ll add knowledge from similar circuits we’ve visited already this year, as well as learnings from the past few races, and this gives us a place to start. The car may behave better when it’s run in a certain condition, in which case we might be willing to compromise on the things that should obviously be good around a certain circuit for a direction from which this car specifically benefits.”

READ MORE: 2020 will be 'much tougher' for Mercedes – Wolff

With few in-season testing opportunities available, the task of testing that baseline car requires the driver to spend a day in a simulator, a facility its engineers are keen to stress is in no way comparable to a video game.

“We start with the basics,” says Norris. “The day begins with a conversation between Will, Jarv [Andrew Jarvis, Norris’ former performance engineer] and myself. We’ll go over our initial ideas for the weekend, and gradually get deeper into it. We’ll recap the previous race, maybe look at what we did differently to Carlos [Sainz] on the other side of the garage, and develop a plan. After that, we’ll spend six or seven hours in the simulator, deciding on a direction.

“Usually, that’s a few runs just getting up to speed, then some proper A/B testing, switching between a baseline and a test with a different downforce level, for instance, or tweaked roll stiffness, or an upgrade part on the car,” adds the 20-year-old rising star. “We’ll try things that Carlos or one of the simulator drivers found useful. The advantage of doing this in the simulator is that the change takes seconds, whereas in the garage, swapping a rear wing or an anti-roll bar might be 20 minutes. We’ll run baseline, change, baseline, change for the rest of the day – or until they kick us out! It really is as simple as that.”

TEAMWORK

Every team operates in a slightly different way but the kernel of driver, race engineer and performance engineer is a standard unit. The complexity of a modern F1 car has made the trackside engineering job more than one person can comfortably deal with, and so the task requires that a race engineer runs the operation, liaising with mechanics and looking after the mechanical set-up of the car, while a performance engineer works closely with the driver, concentrating on driving style and the car's functions controlled via the steering wheel – such as differential settings and brake shapes.

“Often, we’ll be looking at the same things, but with different priorities,” says Joseph. “It’s an over-simplification to say it’s spanners versus electronics – but it’s not far off. It’s more driver-plus-electronics and driver-plus-spanners.”

READ MORE: Sainz thriving in McLaren environment – Seidl

Jarvis, who left McLaren at the end of the 2019 season, adds that his responsibilities concern Norris himself and what he is doing in the cockpit. “I’m much more concerned with the fine details of Lando’s driving,” he says.

“Inevitably that means I’m involved with the electronic systems – what we call the toys – but that feeds into what Will’s doing as well. Think of something like Lando struggling with front-locking over a bump in a braking zone. I could address that by having Lando adjust a setting, or Will could adjust the stiffness of the car.”

REALITY BYTES

The first practice session tends to have multiple aims. Teams will use their 90 minutes of track time to test new parts but also to validate the baseline or answer any lingering set-up questions. Thus, it’s common to see teams tinkering with ride-height or trying different rear wings to identify a preferred downforce level. For the first run of the day, however, the primary concern is getting the driver comfortable and making sure the car – in the broadest possible sense – does what’s expected. Because pits-to-car radios are on open channels, there isn’t much discussion until the driver returns to the garage. Once they’re able to speak in private, debriefing begins.

“After that first run, there’s not a lot of discussion about my driving,” says Norris. “The first run is more about getting a feel: getting to know the braking points, the bumps and generally getting up to speed. Other drivers may do it differently, but for Will, Jarv and myself, we’ll usually restrict the conversation to basic elements such as initial comments on the engine and gear changes, whether there’s oversteer or understeer. We’ll also take a first look at Carlos’ data and see if there’s something obviously different.”

WATCH: The inspiring journey from F1 in Schools participant to McLaren graduate

Joseph adds: “The first thing I want to hear from Lando is if there are any significant problems with the car. I want to know if there’s something that feels wrong with it, or if the balance is not what we expected. Dealing with those issues takes time, and so we need to know immediately.

“The answer is usually ‘no’, and we can all breathe a sigh of relief. After that, the real conversation revolves around whether or not we’ve got a good baseline. If the starting point is good, then the rest of the weekend revolves around making gentle improvements. The most disruptive weekends are the one where you haven’t found a good starting point.”

After FP1, you just want to know anything you can do to make the car go quicker in FP2

However, for all the expert analysis and simulation capability, reality can sometimes bite.

“You can do as many laps as you want on the simulator but still, when you get to the track, it’s real and it’s always different,” says Norris. “That doesn’t invalidate the simulator work, it’s always good preparation – but it isn’t perfect and everything resets for FP1. It could be the wind is blowing from the ‘wrong’ direction, or the tyres aren’t performing as expected, or the latest components on the car haven’t correlated perfectly. You just have to adapt.”

READ MORE: Norris 'lets slip' McLaren MCL35 reveal date

The debrief after the session is where what has initially been a conversation between Norris and his trackside engineers widens, usually via a video conference with engineers at the team’s factory back in the UK.

“After FP1, we’ll probably try to identify in detail how the fundamental balance is, and if Lando felt any difference in the car based on the test items we tried, the tyres we used,” says Joseph. “Then there’s a checklist of items, just to make sure we’re not missing anything. After FP2 you can look in more detail because you have more time and can make changes overnight – but after FP1, you just want to know anything you can do to make the car go quicker in FP2.”

PICKING UP THE PACE

By the time the second session begins, the focus has fully shifted to the race weekend. Teams generally spend the first part of the session testing any set-up options suggested by FP1 data and the debrief. By the midpoint of the session, they will hope to have a clear view on their direction of travel. The second half of the session tends to be devoted to simulation runs: first a qualifying sim, after which a heavy load of fuel is added to the car and the driver is sent back out to spend the final 30-35 minutes of the session simulating a race stint.

After each run, the driver works with his engineers to fine-tune the set-up. “After my initial feedback, Will gets on with running the operation: analysing what I’ve said, and then speaking to the mechanics to outline changes ahead of the next run,” says Norris. “While he does that and the car is being worked on around me, I’ll be speaking to Jarv about my driving. He helps me interpret the data. We’ll be looking at printouts with various laps on an overlay. He’ll point out what worked well – and where I can improve.”

There will be days when I can come in after a run and want nothing but another set of tyres and to go out and give it another go – but I’m easily persuaded to try something else

THE FINAL COUNTDOWN

On Friday evening, the crews habitually strip and rebuild their cars. Race gearboxes and power units are fitted, and extraneous weight is removed. There may also be further set-up changes, with data analysis going on well into the night, often with test drivers putting in the hard simulator yards. The reality is that even if the driver has professed himself happy with the car on Friday afternoon, there’s always something else that can be tested.

READ MORE: The insider's guide to… F1 strategists

“Even if the driver says the car is amazing, I would do exactly the same job as if he’d reported the car was terrible: we’re always trying to find performance,” says Jarvis.

Norris agrees, adding: “There will be days when I can come in after a run and want nothing but another set of tyres and to go out and give it another go – but I’m easily persuaded to try something else. I know how the car is driving – but they’ve got all the information, and the engineering science to back it up.

“It’s the end goal that matters. You want to finish FP3 – final practice – in a place where you’re happy with the car, and any adjustments you’re planning to make for qualifying are minor. It could be with the toys, opening the diff a little, or coming up a hole on the front wing, or adding a millimetre of ride-height. Nothing that’s going to make the car feel different, just something that’s going to give you that little bit more confidence.”

The overriding hope is that, after a smooth build-up through the practice sessions in which the baseline car performed as expected and the team were able to work on fine-tuning the details, the car can go into qualifying and then the race capable of extracting maximum performance – or something very close to it. That’s followed by the elation of a good result or the despair of one that got away – and then those feelings are put in their box and the team starts afresh preparing for the next race, because the challenge and the set-up is going to be completely different once again.

Next Up

Related Articles

Bottas' grid penalty status and each F1 driver's penalty points

Bottas' grid penalty status and each F1 driver's penalty points Facts, stats and trivia ahead of the 2026 Australian GP

Facts, stats and trivia ahead of the 2026 Australian GP/16x9%20single%20image%20-%202026-02-16T093250.724.webp) Why race starts will be different in 2026

Why race starts will be different in 2026 Listen to Carlos Sainz's interview on Beyond The Grid

Listen to Carlos Sainz's interview on Beyond The Grid What is the weather forecast for the Australian Grand Prix?

What is the weather forecast for the Australian Grand Prix? Bottas ‘definitely appreciating’ F1 more after year out

Bottas ‘definitely appreciating’ F1 more after year out