As McLaren reach a momentous half century of Formula One competition, we look back on some personal highlights with former team principal Ron Dennis, now Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of McLaren Technology Group, and the Chairman of McLaren Automotive...

Q: Ron, Monaco will see McLaren celebrate the 50th anniversary of the team’s first Grand Prix (Monaco 1966). For much of the intervening half-century you have been the man shaping the team. Could you please share with us some of your greatest, funniest and most dramatic moments? Can we start with Ron Dennis, the Formula One entrepreneur? When you took over the team in late 1980, Formula One had recently been transformed from a ‘gentleman’s sport’ to a global business, and you helped push that development. Was the moment just right for you?

Ron Dennis: In late 1980 I began the McLaren chapter of my racing career, having started in Formula One way back in 1966, working for Cooper. But, over the 14 years between 1966 and 1980, I had been monitoring the development of Formula One from various different perspectives, and of course I wanted to make a difference at McLaren, and indeed to shape McLaren’s brand.

That important design milestone will go down in history, not least because of the hugely significant safety improvements it introduced.

Q: And probably also make some money?

RD: Making money is a peripheral goal for me – always has been, always will be. Other things motivate me far more compellingly. Besides, from a business point of view, making money is merely the opposite of losing money; losing money means your company is failing, whereas making money means your company is succeeding. And I want McLaren to succeed – again, always have, always will.

Moreover, as a motivating force rather than as an indicator of business success, making money is for me much less important than winning. Winning really matters to me. But if you use the word ‘winning’ in a Formula One context, people tend to think you only mean winning Grands Prix. Of course that is super-important – but I have always wanted to win everything else too. I wanted McLaren to be seen as the most innovative company in Formula One from every perspective; nowadays I want McLaren to be recognised as one of the world’s most advanced and inventive companies across a wide range of hi-tech disciplines, some of them involving racing but many of them unconnected to the sport.

Q: McLaren has always been a technical innovator in Formula One since you took over, hasn’t it?

RD: Right from the start, I was determined that McLaren should utilise every available technology – including technologies that had never before been considered in Formula One. The first carbonfibre Formula One car was a McLaren – the MP4/1 of 1981 – and that important design milestone will go down in history, not least because of the hugely significant safety improvements it introduced. But, actually, the concept behind the MP4/1 was originally conceived by my previous company, Project Four, although that is now a bit of a historian’s footnote, I concede. Besides, the game-changer from a carbonfibre point of view was when our design was launched as the McLaren MP4/1, because the power of the Formula One spotlight and the might of Formula One budgets allowed carbonfibre technology to become a very real catalyst for change.

Additionally, to be able to produce a chassis that was much stronger and much stiffer, opened up the opportunity for us to optimise a technical trend that was becoming more and more performance-critical in Formula One at the time – the ever-increasing forces generated by ground effects – because those forces required very strong, very stiff chassis. So it was a virtuous circle, and McLaren was at the centre of it, in the vanguard of that revolution, and the earliest beneficiary in terms of improved competitiveness: winning, in other words.

But McLaren’s focus on innovation in the early 1980s was not only technical. We also began to think innovatively about how the team should be run – the garaging, the presentation of cars and personnel, and even the design, look and feel of the factory. From day one I wanted the mindset of everyone who was part of McLaren to be inextricably linked to a fervent desire to seek and find perfection.

That world championship was very satisfying – because it was so disciplined. It was definitely not won by luck.

Q: It must have been a pretty brave decision to acquire McLaren in late 1980, given the state the team was then in, having just endured three pretty dismal seasons [1978, 1979 and 1980]. How long did you chew things over before taking the plunge?

RD: Actually [laughs], there was no chewing things over at all. I had already approached Philip Morris [the parent company of Marlboro, the McLaren team’s long-time title sponsor], who were sponsoring not only McLaren in Formula One but also some of the junior teams I had been running in Formula Two, Formula Three and Procar [the one-make series for BMW M1s that supported Grands Prix at the time], and I had tried to convince them that their Formula One sponsorship would be better placed with my company than with McLaren. They thought about that possibility, but they quickly came to the conclusion that the Marlboro-McLaren association was a valuable one from a brand point of view. However, since the McLaren team was not at that point successful, and since I was proposing to run a successful Marlboro-backed Formula One team, the logical extrapolation was that I should take over the McLaren team and make it successful. In 1981 McLaren duly became McLaren International, and we quickly began developing it into a much more modern, much more dynamic, and ultimately much more successful Formula One team. So it was a reverse take-over, so to speak, and it was not aggressive at all. Initially it was a 50:50 deal – but, after 18 months, and to my surprise, Teddy [Mayer, the incumbent McLaren team principal] said he was becoming increasingly concerned about the prohibitive cost of turbocharged engines and was ready to step away, so the opportunity arose for me to acquire a controlling interest in the company, which I immediately did.

Q: You were relatively young then…

RD: Yes, I was 32. I guess you could say it was a pretty challenging time for a young-ish man. I did not have a great deal of money at that time, and, if you do not have a great deal of money, then you need to find someone who shares the same vision and passion as you do, and importantly could help with the funding of a turbocharged engine programme. And that, of course, was Mansour Ojjeh, who went on to join me as a McLaren shareholder in 1984, and who has been my business partner ever since.

Q: Indeed so – and, with that in mind, let’s refocus on the word ‘winning’: 17 of McLaren’s 20 world championships have been won under your reign. Which was the sweetest, which was the most surprising and which was the most unexpected?

RD: Each one was different and each one was imbued with its own highs and lows. But undoubtedly the best will be our next world championship. If you are as ambitious as I am, that is always the case, always has been, always will be. I am the kind of person who looks forward, not backward.

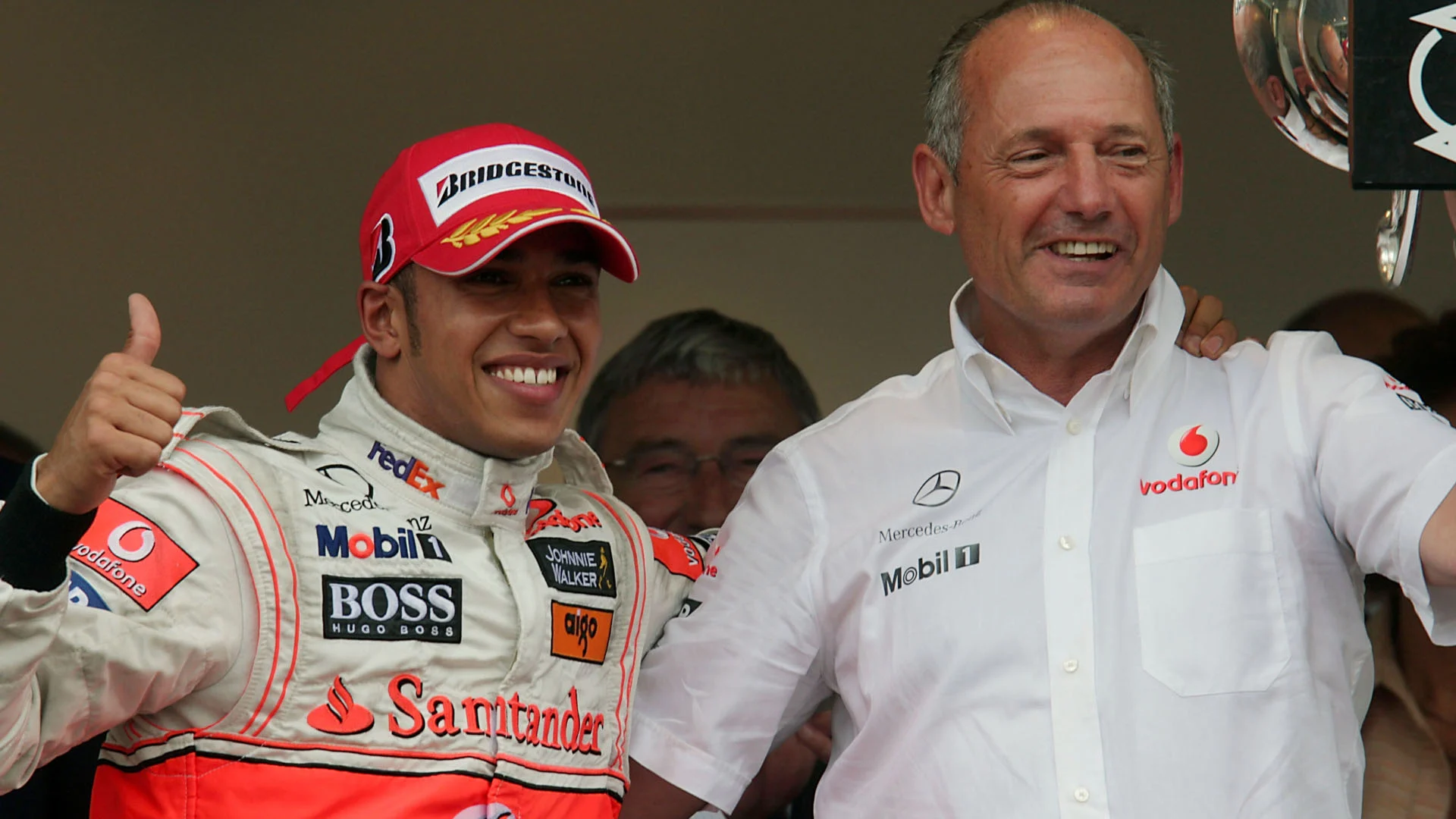

However, since you ask, people tend to regard Lewis’s [Hamilton] 2008 world championship as a bit lucky – because it was won on the last corner of the last lap of the last Grand Prix of the season, as you doubtless recall – but I actually felt it was the most professional. We had had to take very difficult decisions about the final tyre choice, and the unsettled weather conditions made that calculation harder still. One of the most perilous situations you can be in in Formula One is one whereby you do not have to win to win – in other words whereby you do not have to win the race to win the world championship. Well, in that Grand Prix, in Brazil, which was the final race of the season, we only had to finish fifth. That being the case, our approach to the race weekend was extremely cautious, but it was also meticulously controlled. The preceding lap times had shown that Lewis was on course to take the fifth place he required before flag-fall – and, although as things panned out it ended up being a bit too close for comfort, it duly happened. So that world championship was very satisfying – because it was so disciplined. It was definitely not won by luck.

It really was a technological masterpiece. And of course it was a joy to see Ayrton [Senna] dominate that dramatic race in it.

Q: Okay, now I want you to talk about McLaren the technical pioneers: from the carbonfibre monocoque, to brake-steer, to the F-duct, McLaren have consistently broken new ground in Formula One. Which McLaren innovation are you proudest of any why?

RD: The most frustrating innovation was undoubtedly brake-steer – because no sooner had we perfected it than it was revealed by a photographer [Darren Heath], who poked his camera into Mika’s [Hakkinen] car’s footwell after it had retired at the Nurburgring in 1997 and published the resulting image across a double-page spread of the magazine he worked for [F1 Racing], thereby revealing a third pedal for all to see. It was an entirely legal innovation of ours, ingenious and effective, but it was then banned as a result of its having been publicised. That was deeply frustrating.

There have been many other things too: we did not pioneer active ride, but we certainly perfected it. The McLaren MP4/8 that Ayrton [Senna] drove to victory in that spectacular Grand Prix at Donington in 1993 – and four other Grands Prix that year besides – was unbelievably intelligent. It had the ability to reprogramme itself multiple times in a corner, memorise the best place to change gear, and calculate how much braking was needed when and where: it really was a technological masterpiece. And of course it was a joy to see Ayrton dominate that dramatic race in it. That was extremely satisfying.

But what always tops everything for me is Monaco: McLaren has won the Monaco Grand Prix 15 times – which is much much more than any other constructor [Ferrari lies second on the list with nine Monaco wins]. The Monaco Grand Prix really is a magic race to win – demanding yet unique. Sadly, of course, its unique nature dictates that you cannot carry over the year the advantages a car needs to be successful there.

Q: McLaren have built many world championship-winning cars, but is there one for which you have particular affection?

RD: I am very driven by aesthetics. When I look at our cars, my own enthusiasms therefore tend to be a little more influenced by aesthetics than you might expect. On the other hand, I am a firm believer in the adage that form follows function – or, to put it another way, a fast racing car is surprisingly often a beautiful racing car. In fact that paradigm is not restricted only to racing cars – one of my all-time favourite designs is the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird, which is usually referred to as the ‘stealth bomber’. Its design and styling were dictated 100% by function, and yet the result was a strikingly beautiful form.

As far as our cars are concerned, I am consequently very attached to the McLaren-Honda MP4/4, the car that won 15 out of 16 Grands Prix in 1988. It is a wonderfully pure design. And in fact it would and should have won all 16 Grands Prix that year, had Ayrton not crashed into Jean-Louis’ [Schlesser] Williams-Judd while lapping him. Even today, nearly 30 years after the event, Jean-Louis and I always enjoy a humorous exchange on the subject whenever we meet.

Anyway, despite that imperfection, 1988 was a fantastic year for us. And I remember that, some way into the season, I received a phone call from the president of one of our biggest sponsors, complaining that we were winning too many races. And because of his seniority, and because his company were paying a large sponsorship fee, I responded in a suitably tentative and sober way – “Yes, yes, I understand, yes, I will take that into consideration, yes, in the interests of the sport, yes…” – and then, as I put the phone down, I remember it took about 30 seconds for what he had said to sink in, and then I started to laugh my head off. I thought to myself: “You must be joking [laughs]! Do you honestly think we are going to try deliberately to stop winning? Fat chance of me ever authorising that!”

I am very attached to the McLaren-Honda MP4/4, the car that won 15 out of 16 Grands Prix in 1988. It is a wonderfully pure design.

Q: Can you name the sponsor?

RD: Well, as I say, it was one of our biggest sponsors. You could perhaps say it was by some margin one of our biggest sponsors. You do not need to be Einstein to figure it out [laughs]!

Q: Moving on to drivers, you’ve had so many of the greats: Ayrton Senna, Alain Prost, Mika Hakkinen, Niki Lauda, Lewis Hamilton, Fernando Alonso, Jenson Button etc. Which of them has made the most lasting impression on you – and why?

RD: They were, and are, all different. My Formula One career has spanned many many years, and my age in comparison to that of our drivers has been a very relevant influence on my relationship with them. The first driver I ever paid to drive for me, in 1971, was Graham [Hill], who was by that time a double Formula One world champion and something of a racing grandee, yet he was driving my Formula Two car when he was 18 years older than I was [Dennis was 24, Hill 42]. So you can imagine that the relationship I had with him was very different from the relationship I have with Fernando and Jenson now, where the age gap is a little larger but the other way around.

So the dynamics of my relationships with our drivers to a great extent relate to our relative ages – and perhaps the most enjoyable time for me from a friendship-with-drivers point of view was therefore when my age was more or less the same as theirs. We enjoyed similar attitudes and interests – a sort of common worldliness – and things that were interesting to me were also interesting to them. We were joking about girls, we were chatting about having fun – and we did not only talk about it, we actually had a lot of fun together too – but that was because our ages were similar.

Nowadays I would say that the least appropriate thing I could do with Fernando or Jenson, let alone Stoffel [Vandoorne], is go to a nightclub. I think everyone can imagine what kind of impediment I would be to them in such a setting [laughs]. So, coming back to your question, each successful driver has been a favourite of mine for a different reason: I enjoyed different types of favouritism with all of them, and it was very much driven by age.

Q: You have had some amazing drivers racing for you in some amazing cars. Which racing moment lingers most in your memory as the most amazing? And which was the funniest?

RD: I am told I was punching the air when Mika won at Spa in 2000, and I find that very easy to believe. His truly unbelievable move [passing Michael Schumacher as both men were] lapping Ricardo [Zonta] will stay in my memory as long as I live. I think there are very few people in Formula One who would not classify that manoeuvre as an amazing overtake – in fact I would rank it as the all-time absolute pinnacle of overtaking manoeuvres.

Q: Why so?

RD: Our car and Ferrari’s were so evenly matched on the day – and, although Mika had been driving flat-out, relentlessly closing on Michael over the course of the race, Michael was doing a truly phenomenal job of keeping Mika behind once he had finally caught up. So, for Mika to take Eau Rouge flat, on a track that was still damp off-line, and then take a split-second decision to carry momentum out of Eau Rouge and pass into Les Combes not only Ricardo but also Michael, well, Michael must have been so shocked, as he himself was at that same split-second rather more carefully passing Ricardo on the other side. And Ricardo himself must also have been awe-struck – passed on each side by two guided missiles being driven by the two fastest drivers in the world at that time. When I look at that video footage, even now, it makes me smile.

As for funny moments, to be honest I do not spend much time laughing during Grand Prix weekends – a Formula One circuit is an office, really, and as such I conduct business there, and how I behave there is governed by the need to lead by example. Over the years people have often therefore considered me the ‘greyest’ man in Formula One, largely because I tend to appear emotionless on the pit-wall I suppose.

In truth I have always felt that emotion is a bit of a luxury in the context of a Grand Prix weekend, because you do not usually take good decisions when you are emotional; but, yes, there are exceptions, and obviously I was punching the air on the pit-wall at Spa in 2000!

I think Mika [Hakkinen] and Michael [Schumacher] would have been a truly fabulous driver line-up

Q: The best team mate battles: you’ve had driver pairings that were pure dynamite. Which one was most difficult to handle?

RD: The most challenging relationship to manage was that between Ayrton and Alain. Of course, the relationship between Fernando and Lewis had its moments too, but it was different between Alain and Ayrton: they were older, more established, less emotional and more calculating in their rivalry. So that was hard to manage – but, even so, when I look back, I think I did a pretty decent job. Yes, sometimes it was painful; sometimes it was fraught; sometimes it was extremely tense even. Having said that, the fact that they were sitting in the only two cars that could win the world championship, and they were our cars, well, it meant that when I was being tough with them it was pretty hard for them to push back. Yes, they could in theory have said “I won’t drive for you any more”, but of course that would have meant walking out on a possible world championship. So instead they had to toe the line and take the pain [laughs]!

Q: What about the things that never happened? Was there somebody you would love to have joined McLaren, but it never happened?

RD: I shook hands with Gilles [Villeneuve] in early 1982, for him to drive for McLaren the following year. I would love to have had Gilles driving for us. I really rated him. He was a fantastic, and fantastically committed, driver. But of course he was killed in qualifying at Zolder that year: a big loss to our sport and a big loss to McLaren.

Equally, at Monaco the following decade, when he was already driving for Ferrari, Michael [Schumacher] and I agreed for him to drive for McLaren. Our meeting took place not during the Grand Prix weekend; no, we met secretly at a Monaco hotel at another time. But in the end it did not work out because his management insisted on controlling his image rights – they basically wanted to retain them all, plus get paid a lot of money of course. That was disappointing. I think Mika and Michael would have been a truly fabulous driver line-up.

Q: What would you say has been McLaren’s greatest contribution to Formula One?

RD: Without question, the carbonfibre monocoque. It is the biggest single contributing factor to safety there has ever been. Today every serious racing car uses carbonfibre, not only in Formula One but in all major single-seater series.

Q: Formula One in 50 years’ time: what’s your vision?

RD: That would make me 118! I cannot imagine that Formula One will be on my agenda then! But for the next decade I cannot see massive changes coming. The business model will keep everything stable. I absolutely believe that the 2017 regulations will be good for Formula One. Those people who have voiced their opinion that the 2017 regulations will not be good for Formula One are merely people who are trying to maintain their current competitive advantage.

Looking farther ahead, all I can say is that I firmly believe that Formula One will continue to be the pinnacle of motorsport; that it will continue to delight tens if not hundreds of millions of fans all over the world, watching Grands Prix on whatever devices will be fashionable and popular by that time; and that McLaren-Honda will be winning Formula One races and world championships.

Next Up

Related Articles

Exploring fashion star Zhou Guanyu's style journey

Exploring fashion star Zhou Guanyu's style journey Top 10 rookie drivers to score points on F1 debut

Top 10 rookie drivers to score points on F1 debut Verstappen 'the perfect age' to be competing in Nurburgring 24 Hours

Verstappen 'the perfect age' to be competing in Nurburgring 24 Hours F1 Fantasy strategies for China and Japan

F1 Fantasy strategies for China and Japan McLaren need to 'step it up as much as possible' – Norris

McLaren need to 'step it up as much as possible' – Norris How to stream the 2026 Chinese Grand Prix on F1 TV Premium

How to stream the 2026 Chinese Grand Prix on F1 TV Premium