The idea of using the underside of a racing car to generate negative pressure and effectively suck the car towards the track had first been exploited in the Can-Am sports cars series in the 1960s. But they were cars with wide, wheel-enclosing, bodywork. Getting the principle to work on a skinny-bodied, open-wheel single seater initially seemed unfeasible. The car which made that breakthrough was the Lotus 78 of 1977, which ushered F1 into the era of ground effect. Forty years ago, the 78’s successor, the Lotus 79, became the first ground effect car to win the world championship, with Mario Andretti at the wheel.

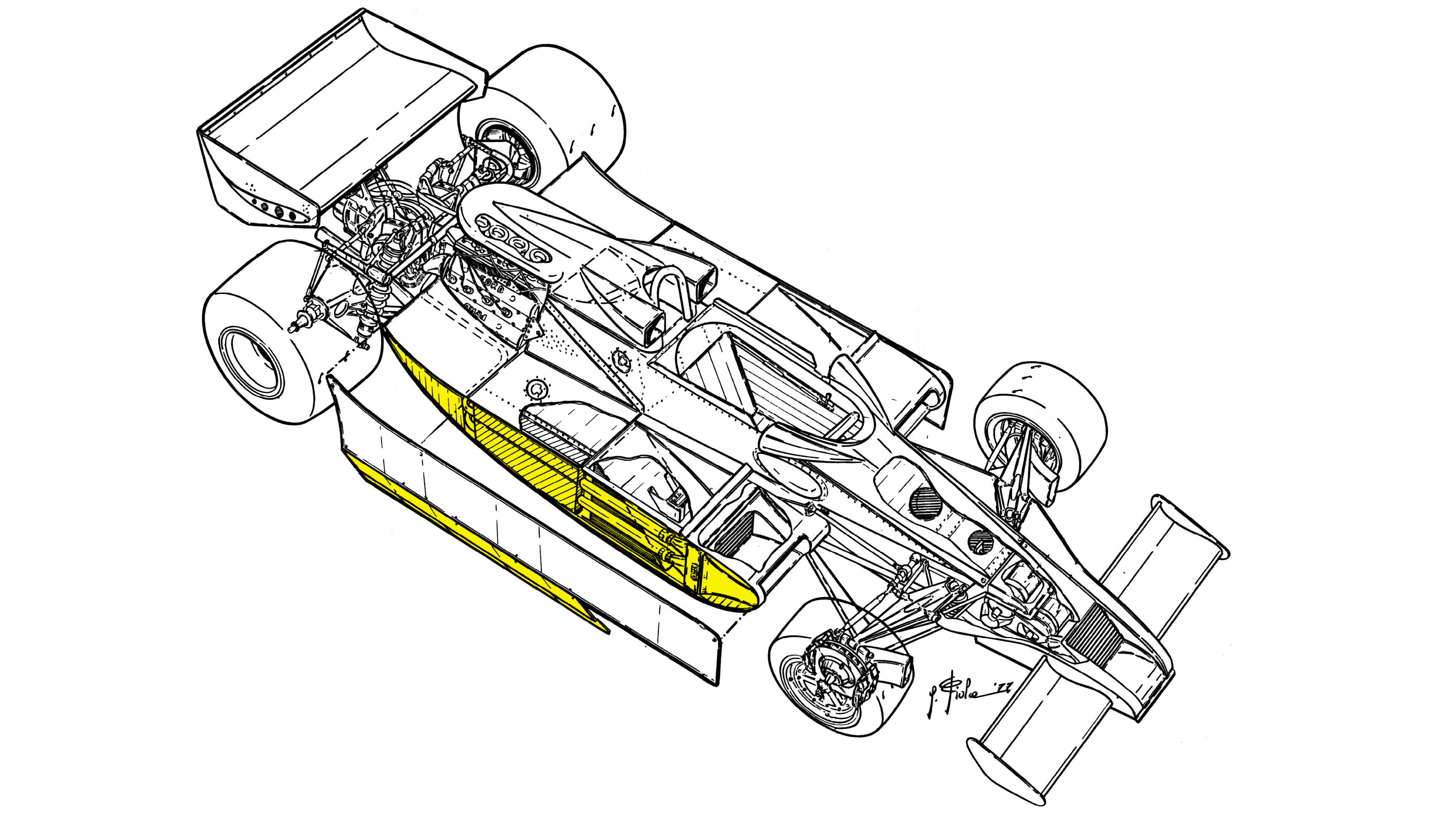

The proportions of the 78 (as seen in the image below) were very different to those of its contemporaries, and therein lay the clue to the radically different way its aerodynamics worked. The central tub was unusually narrow and the sidepods took up a far bigger proportion of the car’s width, while running along the bottom of those sidepods were skirts – brushes initially, later solid nylon. Those skirts were to make a seal between the underbody and the road, a crucial part in propagating negative pressure beneath the car. That negative pressure was created by the internal shaping of the sidepods, which had an opening at the front, close up behind the front suspension, ostensibly to feed the radiators that were placed there. However, it was the placement and angle of those radiators, and the shaping of the auxiliary fuel tanks also housed within the sidepods, that created the internal venturi shape so crucial in exploiting the airflow. The channel the air passed through changed in section as it went back, with a narrow inlet opening into a central ‘throat’ and then a further sudden expansion into a diffuser at the sidepod exit just ahead of the rear wheel and suspension.

Airflow follows the Bernoulli principle whereby the pressure reduces as its speed increases – the venturi shape manipulating the airflow to accelerate and thereby reduce the pressure. But further than that, the close proximity to the ground of the sidepod’s entry massively magnified the effect by accelerating the air as it was sucked through the small gap between track surface and the bottom of the radiator. The increase in air speed as the gap between the road surface and opening is narrowed is vastly more than proportional – i.e. it speeds up very suddenly indeed as the gap closes to almost nothing (hence ‘ground effect’). With the skirts then preventing the air from escaping out of the sides, the acceleration of the air through the channel – and therefore its pressure reduction – was spectacular. This lower pressure applied across the full width of the floor. The difference between the underfloor’s air pressure and that of the much higher-pressure freestream airflow above meant the car was effectively being sucked to the ground. Furthermore, that downforce created hardly any drag, unlike that created by the upper body wings pressing down upon the car.

Engineers Peter Wright and Tony Rudd had worked on the concept in a wind tunnel when they were at the BRM team in the late ‘60s, but that model did not have skirts and the study was abandoned. By the mid-70s they were at Lotus, and when team boss Colin Chapman assigned them the task of re-considering the basic configuration of an F1 car, they recalled their BRM experiments and went to the wind tunnel to investigate further. Initial experiments without skirts showed some promise. But when fitted with skirts the model actually pulled the wind tunnel’s moving belt upwards – and that was the magic moment they realised they’d cracked the code of ground effect on an open-wheeled single-seater. Working around this concept, the car was designed by Ralph Bellamy and Tony Southgate and was testing in secret with Mario Andretti by mid-1976. It made its debut at the opening race of the 1977 season, in Argentina, and Andretti gave the car its first victory at Long Beach three races later.

The downforce generated by the floor is a multiplication of the negative pressure and the area over which it’s applied. Hence not only was the car of the maximum width allowed by the regulations, it was also longer in wheelbase than was typical of the time so as to give the maximum length of floor. Initially, tightly-compressed nylon brushes were used as side skirts, as there were doubts that solid skirts would be allowed as they would need to be moveable to allow for bumps in the track and changes in the car’s attitude. Moveable aerodynamic devices were banned. The brushes were obviously rather more porous, allowing air to escape, but when it was pointed out that both Brabham and McLaren had used rubber skirts some years earlier (for the completely different purpose of diverting air away from the underfloor), it was realised that a precedent had been set, and although the car was launched with the ‘draft excluder’ brushes, it raced with solid nylon skirts. These kept a seal with the track even over bumps and even as the car pitched, dived and rolled. This was achieved through a spring mechanism, being sucked up by the low pressure underfloor and pushed down by the springs. To prevent excessive wear, the bottom of the skirts had tough Teflon-like strips. These were later superseded by even tougher ceramic tips.

It took a few races before the car’s full potential was apparent. Initially, it was no more than competitive with the best conventional cars. The venturi shape was fixed and it brought the centre of aerodynamic pressure further forwards than was ideal, necessitating a bigger rear wing to balance the car, which meant it suffered high drag and was slow on the straights. But into and through the corners Andretti and team mate Gunnar Nilsson were enjoying a downforce advantage of around 15% over the best of the rest.

At Zolder, for round five, Andretti set pole by the margin of 1.5s over John Watson’s Brabham-Alfa – and the F1 world finally realised there was something very trick about the 78. Chapman had not been present when Andretti had set that time, and when he later turned up, he was reportedly furious with his driver for revealing the full extent of the car’s performance advantage. Nilsson won that race and Andretti would later win a further three. It could have been many more, but for the unreliability of Andretti’s special development Nicholson Cosworth engines – and it was this which kept him from that year’s title, which was clinched by Niki Lauda in a non-ground effect Ferrari.

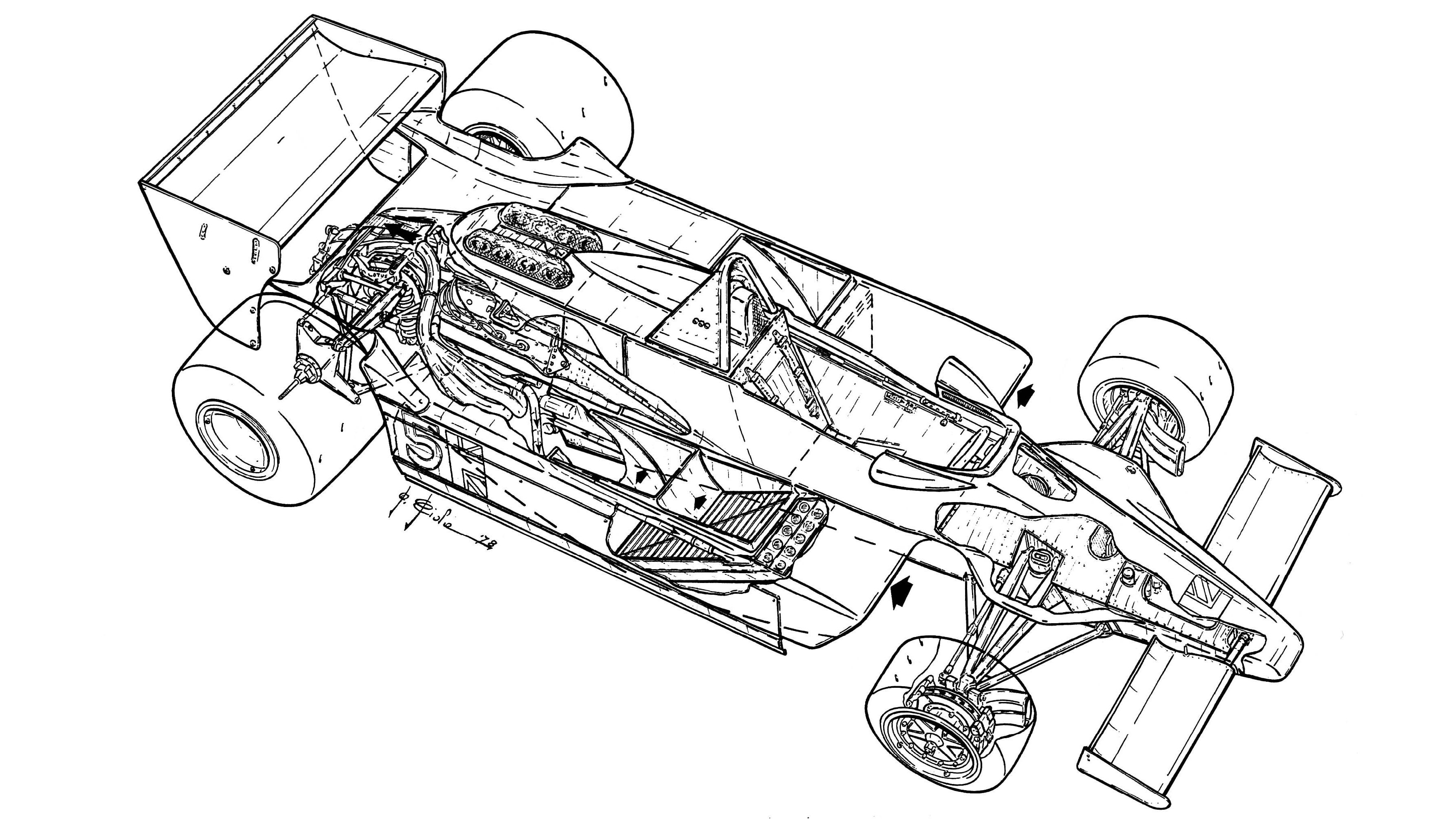

For the following year, the 78’s more obvious flaws were corrected with a new design, the Lotus 79 (see image above), but the 78 was used early season and was still the fastest thing around, Andretti and Ronnie Peterson winning a race apiece in it. With these victories and later ones with the 79 model, Andretti and Peterson finished one-two in the 1978 drivers’ championship (though Peterson was tragically killed at Monza with two races still to go).

The Lotus 78 had initiated a revolution and this concept of car would bring ever-more spectacular gains as the principle was more fully exploited over the years – until eventually it was outlawed by the flat-bottom regulations of 1983. In time, teams would find ways of creating underfloor ground effect without sidepod venturis or side skirts, but it was the Lotus 78 and 79 which showed what was there to be gained.