Monza places a uniquely dominant requirement upon drag reduction, given the track’s elongated straights and relatively few corners. Although the standard response to that from teams is to fit super-skinny rear wings, there is more to it than that. The inherent traits of the car will determine choices not only in the actual wing levels, but also in the details those choices impose…

Bigger wing alternative

At Monza, Williams ran with a significantly bigger rear-wing flap area than any other car. © Manuel Goria / Sutton Images

A car with a rear instability problem may choose not to go full skinny with its rear wing, particularly if it has a strong engine. Hence we saw Williams run at Monza with a significantly bigger flap area than any other car. The lap time differences between this and a conventional flatter Monza wing are not actually huge – because the increased corner speeds carry into faster speeds in the early part of the straight. In terms of lap time, the crucial point is the amount of time taken to get down the total straight rather than how great the end-of-straight speed is.

However, the slower end-of-straight speeds of the bigger wing make you vulnerable to other cars overtaking you. In the race we saw that Williams duo Lance Stroll and Sergey Sirotkin were able to run at the back of the Haas-Force India-Renault train and be towed along by them, keeping the bigger-winged Williams out of reach of the pack behind. This resulted in the team’s first double points finish of the season.

Power considerations

Red Bull ran with an almost flat wing flap of tiny surface area. © Giorgio Piola

At the other end of the scale from Williams, a car with good inherent downforce from its underbody but a power shortfall, would tend to go extreme with how far it trimmed back its rear wings. The best example of this at Monza was Red Bull, with an almost flat wing flap of tiny surface area. This helped the car to reasonable end-of-straight speeds (which helped Max Verstappen fend off Valtteri Bottas for many laps) but probably cost some lap time. However, the small improvement in lap time some extra flap angle may have found would almost certainly not have found the car any grid position improvement – hence its race-ability was prioritised.

DRS flap detail

On Toro Rosso’s Monza wing, the DRS mechanism featured two fixings to give the required range of movement for the DRS flap. © Giorgio Piola

The implications of the DRS activation at such high speeds and with such small flaps can be significant. Marcus Ericsson suffered a huge crash on Friday afternoon when his Sauber’s DRS failed to close as he stood on the brakes for the first chicane. Rearward-facing footage showed that a moment before he began braking, with the car well in excess of 300km/h, the flap was forced upward. This seems to have forced the flap off its DRS mechanism’s teeth, meaning it was unable to close even when the hydraulic pressure was automatically applied as Ericsson stood on the brakes. Such was the small angle between the main plane and flap on the Toro Rosso’s Monza wing that, uniquely, the DRS mechanism featured two fixings to give the required range of movement for the DRS flap.

Balancing the aero

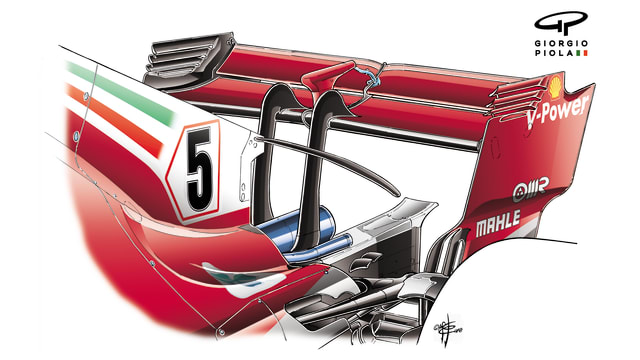

To retain aero balance, Mercedes introduced a subtly re-profiled and slightly smaller top flap. © Giorgio Piola

Running such tiny rear wings means an appropriate reduction in front wing angles so as to retain the car’s usual aero balance. But if this takes the front wing into an area of inefficiency (i.e. it doesn’t lose as much drag as appropriate for the reduction in downforce), teams may actually use smaller flaps – and Mercedes did so at Monza, with a subtly re-profiled and slightly smaller top flap.

You only had to look at Lewis Hamilton’s rapid race pace to see this was a change worth making…